Eduardo Porter is Still Wrong About UBI and AI: A Response to The Guardian

Universal Basic Income Isn’t a Job Replacement Plan—It’s an AI Dividend and Stable Income Floor That Protects Work, Wages, and Democracy

Eduardo Porter’s new Guardian piece is built around a familiar move: treat universal basic income as a single, maximalist policy meant to replace paychecks, then declare it either unaffordable or socially corrosive, then pivot to means-tested wage subsidies as the “serious” alternative. This time the villain is AI. The structure is the same as last time. He even opens by mocking UBI as a “space zombie,” a sci-fi idea that keeps crawling back no matter how many times critics think they’ve killed it.

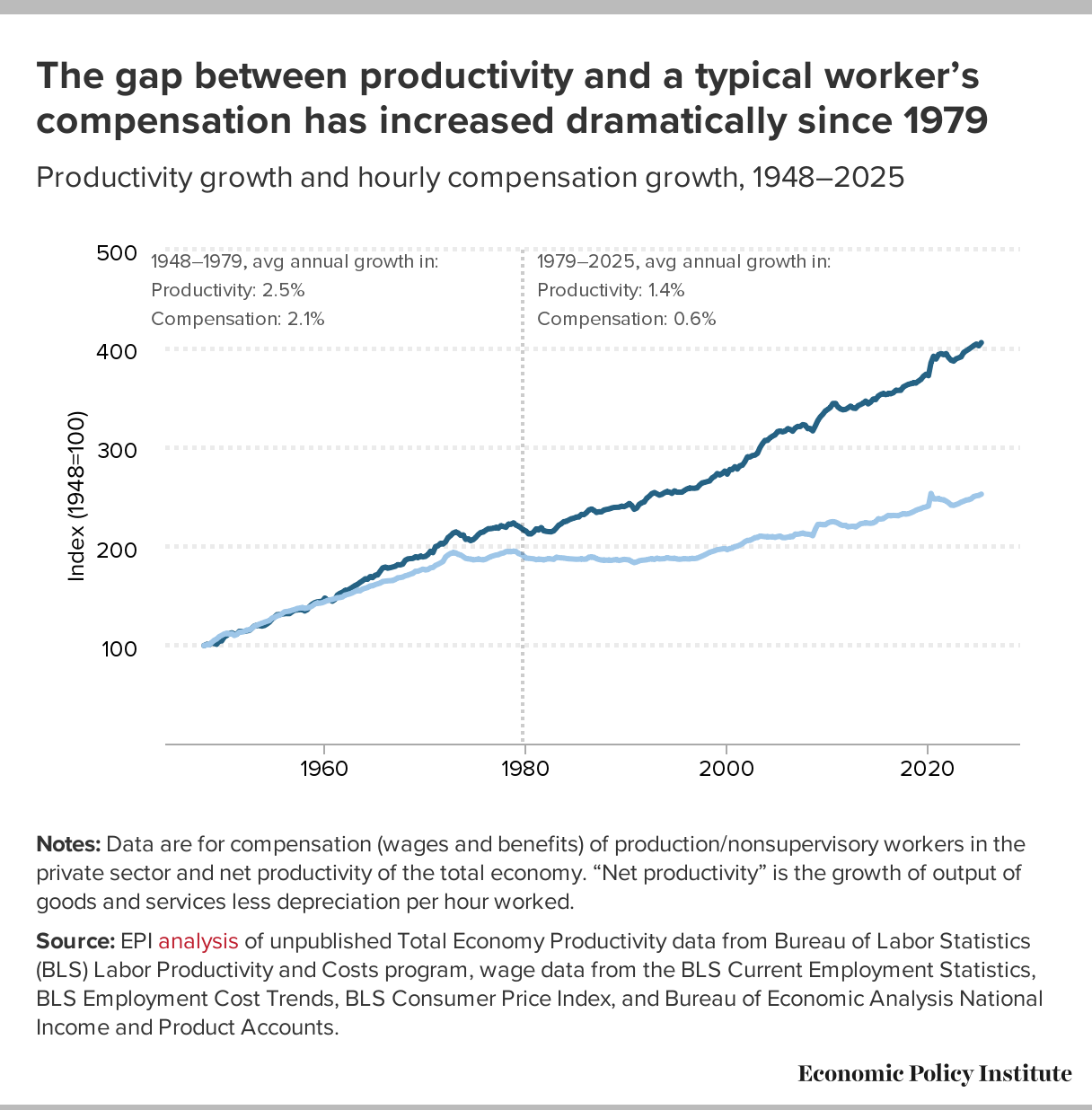

The reason it keeps coming back is not Silicon Valley fad-cycling. It keeps coming back because the problems it addresses have kept getting worse for half a century: rising productivity with relatively stagnant wages, growing insecurity, a safety net that a significant percentage of people fall through, and an economy that increasingly rewards ownership over labor. AI does not create those problems. AI accelerates them.

Porter has changed in one meaningful way since he went after UBI in 2016. He now takes the tech disruption of the labor market story more seriously. He now acknowledges that AI can hammer job security, reshape bargaining power, and intensify the distributional fight over who captures new productivity. That is growth.

He has not changed in the way that matters. He still argues against UBI by arguing against a policy that UBI advocates are not proposing. He loves building straw men.

Foreword to Civilization is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber here or on Patreon.

What Porter Got Closer To, And What He Still Misses

Back in 2016, Porter argued in the New York Times that UBI was a poor tool to fight poverty and leaned heavily on two claims: it would be ruinously expensive, and it would reduce work. The expense claim relied on multiplying a big check by a big population as if gross cost were UBI’s meaningful cost. The work claim leaned on a moral story about effort rather than the evidence he himself previously cited on pilots.

That contradiction is why I called him out then. He highlighted evidence showing no meaningful work collapse in the pilots he chose to discuss, then turned around and warned that UBI would make people stop working. I pointed out the hypocrisy plainly: praising a result and then denying it in the very next breath is not analysis, it’s agenda.

In 2025, Porter now repeats the same pattern with updated props. He admits AI could destroy or degrade jobs and wages, then treats that as a reason to reject UBI anyway. He argues that if the AI future is bleak, a broad consumption tax is “ridiculous,” and if the AI future is not bleak, UBI is unnecessary.

That is not a critique. It’s a heads-I-win-tails-you-lose pseudo-intellectual trap.

The First Fix: Stop Pretending UBI Means “No One Works”

UBI is not meant to replace the income from all jobs. UBI is meant to ensure nobody falls below a non-zero floor, and to distribute a dividend from an economy we all help create. The floor is the point. The dividend is the justice.

Put in the simplest terms: UBI is a foundation. All income is earned on top of it. A poverty-line UBI is not “the replacement paycheck for the post-work apocalypse.” It’s the equivalent of the foundation of a house. It’s so the house built on top of it doesn’t crumble and fall. It prevents the worst outcomes, stabilizes consumer demand, and gives people leverage to say no to exploitation.

Porter keeps fighting a fictional UBI where everyone gets a middle-class wage from the government and the labor market disappears. He even waves at a fantasy number—“give everyone the median income”—then declares it would cost $14 trillion and therefore the entire concept is unserious.

That is like “critiquing” public schools by multiplying the price of private boarding school for every child and calling public education impossible.

AI Job Loss Is Not 100%. It’s Still Massive. The Right Range Is The Point.

There are two childish stories about AI and jobs. One says AI ends all jobs. The other says everything will be fine.

The reality is a wide band of disruption that can be measured in chunks of the labor market large enough to break lives and politics, but not so large that society becomes a sci-fi desert of total idleness. I have been arguing for years that the most realistic path is not instant total unemployment. It is rapid labor market churn, wage pressure, and a race down the job ladder.

That “middle path” now has plenty of backing:

- A 2025 World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report concluded that 22% of jobs are expected to be disrupted by 2030.

- A 2025 study jointly published by the Gerald Huff Fund for Humanity and the National Science Foundation concluded that 25% of jobs could be disrupted by 2028.

- A 2023 report by McKinsey estimated that 30% of hours worked in the U.S. could be automated by 2030.

- A 2023 Goldman Sachs report estimated that two-thirds of jobs are to some degree exposed to automation and that 25% to 50% of work in those exposed jobs could be replaced by 2033.

- MIT’s Project Iceberg has an “Iceberg Index” estimating that current AI systems already overlap with about 11.7% of U.S. labor market wage value in technical capability terms.

That 10% to 25% zone is the disruption Porter should be able to see clearly. It is not the “end of work.” It is the end of stability for many of those who still have some.

Additionally, the spending of UBI will create more jobs for people to take. Without UBI, the net job losses will be larger than without UBI.

Demand Is The Hidden Variable Porter Barely Touches

Porter’s Guardian piece nods at AI and jobs, but it still treats employment as if it’s determined primarily by worker incentives. It is not. Demand creates jobs. People with money create demand. People without money create layoffs.

I laid this out in detail in 2023 with a simple, realistic model: AI makes some workers more productive, firms need fewer workers for the same output, and whether those workers keep jobs depends on whether there is enough consumer demand for the firm to expand rather than cut.

UBI’s macro job effect is not a mystery. A floor under everyone’s income is an automatic stabilizer. It keeps spending from collapsing during displacement shocks. It reduces the odds that productivity gains translate into demand shortfalls and cascading layoffs.

There will always be some amount of demand for human labor, no matter the cost or quality of AI-created goods and services. Just as some people choose to spend more for organic foods, some will choose to spend more on human goods and services.

The Second Fix: Stop Using Gross Cost As Propaganda

Porter’s favorite move is arithmetic theater: multiply a universal check by the population and call the result “the cost,” as if taxes, benefit offsets, and savings mechanisms do not exist.

UBI cost debates that start and end with gross cost are not serious.

Here is the serious part: the net cost of a poverty-line UBI, with realistic offsets and tax phaseout, is not remotely the apocalyptic number critics love to chant. A new working paper by Karl Widerquist and Jack Rossbach updates “back-of-the-envelope” UBI costing with 2024 data and finds that a UBI set at $16,000 per adult and $8,000 per child (with a 50% phaseout accomplished via taxes) has a net cost of around $605.5 to $649.2 billion per year, roughly 2.07% to 2.29% of GDP.

The most important point is not even the dollar figure. It’s the trend: as a share of GDP, a poverty-line UBI has gotten cheaper for more than 50 years—down from about 6.22% of GDP in 1970, to around 2% today.

So when Porter treats UBI as a futuristic luxury that becomes plausible only after some imagined AI endpoint, he is historically backward. If anything, the 1970s were the time to begin. That was when wages first decoupled from productivity and growing insecurity and inequality became government policy.

UBI is entirely affordable, and a poverty-line floor is more affordable now than it was when the modern wage-productivity split began.

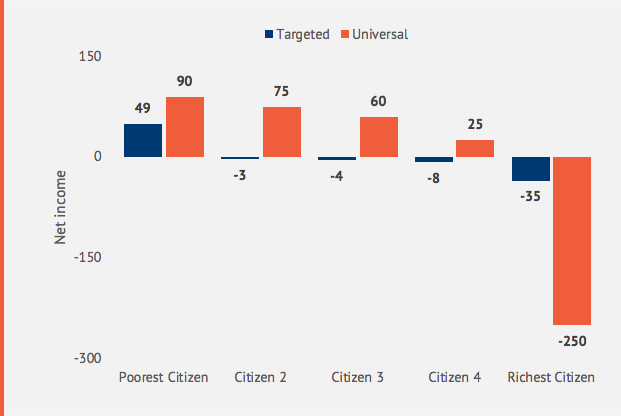

The Third Fix: Universality Is Not Waste. It’s The Design.

Porter continues to treat universality as a fatal flaw: money “wasted” on people who do not “need” it. That view confuses accounting with political economy.

Universality is what makes a floor durable. Universality is what makes it automatic. Universality is what makes it non-punitive. Universality is what makes it trusted.

Means-tested programs train people to fear the system and actively discourage people from increasing their incomes. They are booby-trapped with cliffs, paperwork, surveillance, and stigma. They punish volatility in income precisely when volatility becomes the norm. They exclude via bureaucratic testing those who need help the most. That is all the opposite of what you need in an AI-impacted labor market.

Porter’s preferred substitute—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) wage subsidy—does something even worse: it ties survival more tightly to wages. It explicitly excludes the unpaid work that keeps society alive: caregiving, volunteering, community building. If you do not have taxable earnings, you do not count.

UBI counts everyone. That is the point.

The Dividend Argument Porter Still Refuses To Take Seriously

Porter concedes that capital owners will capture a disproportionate share of AI’s gains and suggests heavier taxation of capital. Fine. That is part of the answer.

But taxation alone still frames the public as petitioners. UBI reframes the public as dividend-earning shareholders.

AI is built on a mountain of collective inheritance: publicly funded research, public universities, decades of government grants, and training data produced by billions of people—living and dead—who were never asked, never compensated, and never given a share certificate.

Gar Alperovitz puts the moral core cleanly: most modern income exceeds what anyone can claim as the product of their own work in the present; it is “a gift of the past,” a technological inheritance. That inheritance is currently routed upward by default. A universal dividend is how you route a portion back downward by right.

Porter’s alternative is still paternalistic. He wants targeted help for the poor and wage subsidies for workers. That is how you build a permanently anxious majority watching a permanently secure minority.

A universal dividend is how you build a shareholder society that includes everyone.

And universal provision builds pressure to tax the rich more than targeting ever can.

UBI Reduces Inequality In Several Direct Channels

Porter waves at inequality and implies UBI is too blunt to matter. That is wrong in at least four ways.

- Consumption inequality falls immediately because the floor raises the bottom mechanically.

- Bargaining power rises because the threat of destitution is removed. When survival is not on the line, saying “no” becomes possible. Wages rise at the bottom because employers lose the ability to weaponize hunger and homelessness.

- Unions strengthen because UBI functions as a universal, unlimited-time strike fund. The ability to withhold labor without starvation is what makes collective bargaining real.

- Democratic participation rises because time and stress are freed up. That means more organizing, more volunteering, more small-donor politics, and fewer people trapped in the learned helplessness that inequality manufactures.

UBI is not a cure-all. It is the platform that makes other equalizing reforms easier to win and easier to sustain.

Financing: Porter’s “VAT and Income Tax Won’t Work” Claim Is Just Slogan

Porter dismisses income taxation and mocks VAT-style approaches in a future with less work. This is where the critique collapses into vibes.

A modern UBI can be financed by a portfolio, not a single tax:

- progressive income taxes and reforms

- consumption taxes and transaction taxes

- wealth taxes and estate taxes

- land value taxation

- corporate taxation and excess profit mechanisms

- requiring large corporations to issue new stock annually into a National Wealth Fund, diluting shareholder value to fund the universal dividend

Even Porter’s own instincts point toward the real destination: broaden ownership. The difference is that UBI advocates are willing to make that destination universal and automatic, instead of conditional and stigmatized.

Also, taxation is not the only lever. In a world where AI drives disinflationary pressure by lowering costs and compressing wages, some portion of a UBI floor can be treated as macro stabilization, similar in spirit to the pandemic-era recognition that governments can and do create and issue money.

Porter treats that as unthinkable. Recent history says otherwise.

The Missing Layer In Porter’s Work Story: Security, Stress, Democracy

Porter keeps returning to the fear that if people have income, they will work less, and that this is inherently bad.

Even if it were true at the margin, it is not a moral failure. It is a social upgrade. Less forced labor, less desperation employment, more care work, more education, more entrepreneurship, more civic participation.

But the deeper point is what insecurity does to a society.

A chronically stressed population is sicker, angrier, more violent, and easier to radicalize. Insecurity consumes cognitive bandwidth. It increases receptivity to scapegoating and authoritarian “order” narratives. I have argued explicitly that reducing insecurity and inequality is a democratic necessity, not a lifestyle perk.

Universality matters here again. When government delivers a tangible benefit to everyone, it signals inherent worth, builds trust, and reduces the corrosive politics of “makers vs takers.” A universal dividend is not just redistribution. It is social cohesion.

The Real Package: UBI As Floor, Plus A Time Dividend, Plus Public Options

UBI is the foundation, not any kind of ceiling.

A serious “AI economy” agenda stacks policies:

- UBI as a poverty-ending floor that grows with productivity

- universal healthcare so survival is not tied to employment

- shorter workweeks and shorter workdays with no loss in pay so productivity gains become time, not just profit

- stronger collective bargaining rights and antitrust enforcement

- public investment and, if necessary, public employment for socially necessary work that the market underprovides

Porter writes as if rejecting UBI preserves work. In reality, rejecting UBI preserves desperation.

The Bottom Line Porter Keeps Dodging

UBI is not a plan for a world with no jobs. It is a plan for a world where jobs are less reliable as the sole delivery mechanism for survival and dignity.

AI disruption in the 10% to 25% range is not speculative fantasy anymore. It is visible in exposure measures and credible institutional estimates.

A poverty-line UBI is not fiscally absurd, and arguably never has been. The newest costing work suggests it is on the order of about 2% of GDP on net, and it has gotten cheaper as a share of GDP for decades. The cost to directly end poverty with UBI has never been lower than it is now.

And the moral logic is not radical. It is inheritance. Most wealth is built on a collective gift of the past. A universal dividend is a modest, sane way to distribute a portion of that gift to everyone alive now, including the caregivers, volunteers, and unpaid workers all of whom Porter’s preferred policies leave behind.

Porter has grown enough to see AI as a distributional threat. He has not grown enough to stop fighting a straw man UBI that serious advocates are not proposing. He is still arguing against “universal basic income replacing work,” while the actual case is “universal basic income preventing poverty, lessening insecurity, stabilizing demand, reducing inequality, and distributing an earned inheritance to all so that AI literally WORKS FOR EVERYONE.”

If you enjoyed this article, please share it and click the subscribe button. Also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my work to have your name appear below.

Special thanks to my monthly patrons: Gisele Huff, Haroon Mokhtarzada, Steven Grimm, Bob Weishaar, Judith Bliss, Lowell Aronoff, Jessica Chew, Katie Moussouris, David Ruark, Tricia Garrett, A.W.R., Daryl Smith, Larry Cohen, John Steinberger, Philip Rosedale, Liya Brook, Frederick Weber, Dylan Hirsch-Shell, Tom Cooper, Joanna Zarach, Mgmguy, Albert Wenger, Andrew Yang, Peter T Knight, Michael Finney, David Ihnen, Steve Roth, Miki Phagan, Walter Schaerer, Elizabeth Corker, Albert Daniel Brockman, Natalie Foster, Joe Ballou, Arjun Banker, Tommy Caruso, Felix Ling, Jocelyn Hockings, Mark Donovan, Jason Clark, Chuck Cordes, Mark Broadgate, Leslie Kausch, Juro Antal, centuryfalcon64, Deanna McHugh, Stephen Castro-Starkey, David Allen, Liz, and all my other monthly patrons on Patreon for their support.

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.