What is There to Learn From Finland’s Basic Income Experiment? Did It Succeed or Fail?

Evaluating the Preliminary Results of a Partial UBI and Slightly Less Bureaucracy

Update: Since I published this article, the official final report was released in early 2020. You can read a summary of the findings here.

After two years of experimentation within a two-year experimental design, Finland released on February 8, 2019, preliminary results of their basic income experiment. For anyone who reads the full report, it can be considered nothing short of both promising and fascinating, but what it can’t be called is complete, because the results are still preliminary and based on only the first half of the experiment.

With that said, as is also true of the experiments in the U.S. and Canada in the 1970s, there are certainly some conclusions that can and can’t be drawn within the proper context of the experiment’s design. But to reach these conclusions, we’ll first need to go over some of the nitty-gritty details of how the experiment was designed, and what it didn’t even try to measure.

The Context

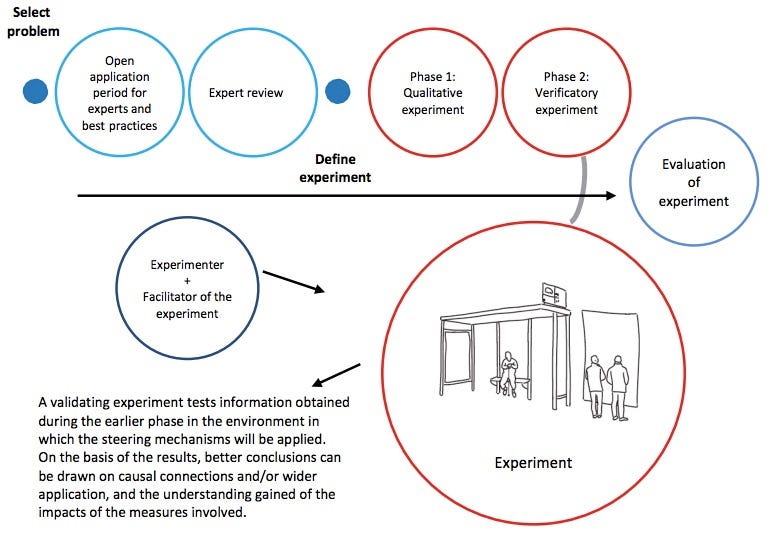

Finland’s experiment rocked the headlines of the world when it was announced back in 2015. What went under the headlines was that this experiment was to be part of a new Finland where the scientific method would be applied to public policy. It would be a landmark in the history of policy making where instead of endlessly speculating and arguing, potential new policies would be considered, tested, and compared to existing policies and other alternative policies, before implementing what was found to be the best one. Finland’s goal was to become the first truly experimental nation in the world, where policies are based on science, not ideologies or myths.

It is within this context that experimenting with basic income began its way through a process where what was once hoped to be a grand first in finally putting the idea of unconditional basic income to the test at a national level became a not-so-grand test of slightly less conditional unemployment benefits. The question transformed from “What would a random person do if provided an unconditional basic income instead of most existing conditional benefits, and what would the effect then be on both the individual and society?” to “What would an unemployed person do if provided a partial basic income in addition to many existing conditional benefits, and what would the effect be on only the individual?”

That may seem like a fairly small difference, but it’s actually quite large. You see, unconditional basic income is meant to be about entire communities, not just the individuals within those communities. It’s about universalism. That’s where the bulk of its effects emerge, from universal application. It’s also mostly about the employed, because most members of society are employed. To only test the unemployed is to therefore miss out on how most of the population would be impacted by UBI.

To be fair to the researchers, they knew this. They are scientists trained in science. Politicians however are not, and politicians are the ones who ultimately made the decisions. As a result, the experiment as implemented was extremely limited in design, and given the opportunity to expand the experiment from only looking at the unemployed to looking at the employed as well, Finland’s politicians, the same ones who claim to want an evidence-based Finland, chose to keep the experiment limited in scope.

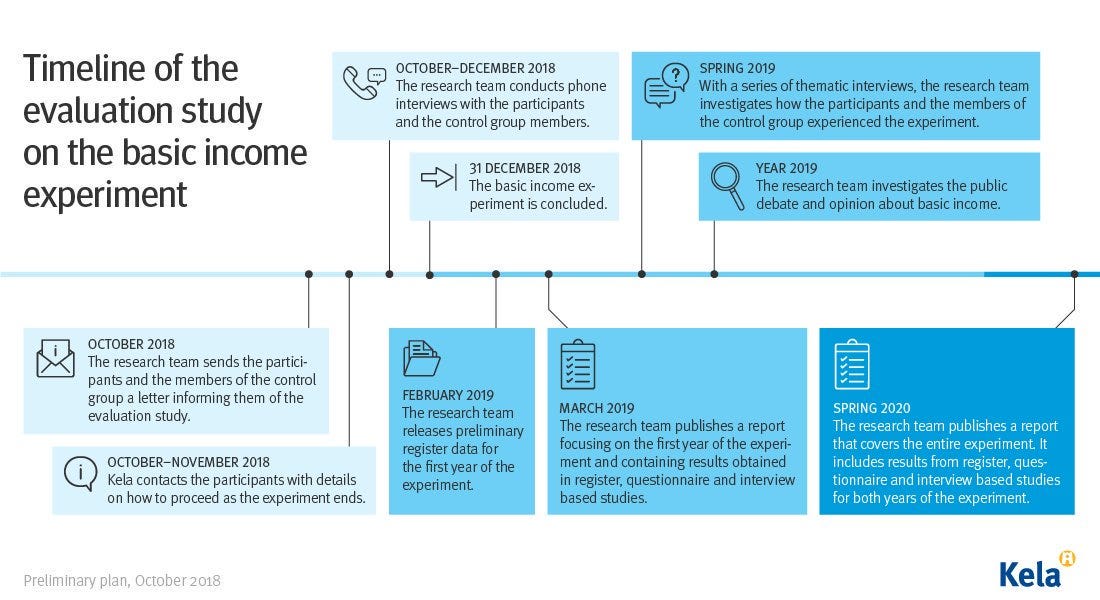

Finland of course never canceled their experiment, despite all the headlines written to the contrary. It was a two-year experiment that took place over 2017 and 2018. Because of the way data is available for research in Finland, there is a year gap, so the employment data from 2017 is available in 2019, and the data from 2018 will not be available until 2020. Thus the evaluation phase of the experiment will not be fully completed until next year.

It is within this context, that we need to understand Finland’s experiment, and how it really wasn’t a test of UBI. It was a test of slightly reducing the marginal tax rates experienced by the unemployed, and also slightly reducing the amount of bureaucracy they experience. Both of course are elements of UBI, and so there is still information to learn from such an experiment, but we must be careful with what conclusions can and should not be drawn, and it requires some knowledge of scientific methodology to fully appreciate why.

The Experiment

As a quick introduction to scientific experimentation, by creating two groups that are mostly identical to each other (preferably through random selection) by changing one variable in one group (the treatment group) and leaving the other group unchanged (the control group), we can determine what are the effects of manipulating that variable on other variables we’re interested in. What we change is called the independent variable, and what is changed as a result are the dependent variables.

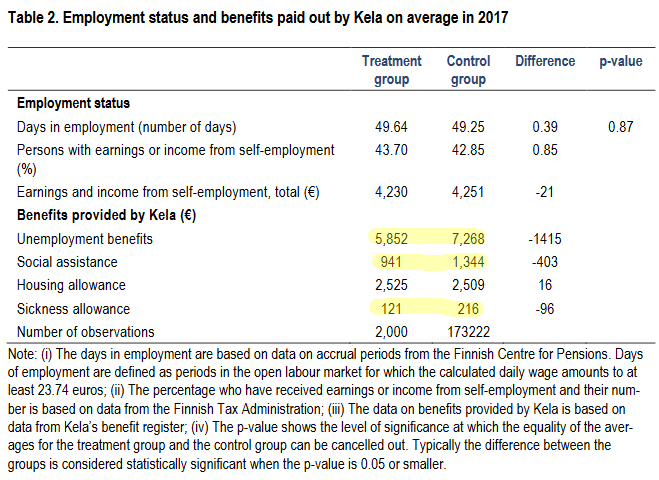

In Finland’s experiment, the control group was 173,222 unemployed Finns. The treatment group was a randomly selected group of 2,000 also unemployed Finns. You may think how the experiment was run, was to give them basic income instead of unemployment benefits, but you would be mostly wrong, and only partially right. The single greatest problem with the design of the basic income experiment, aside from the exclusion of employed Finns, and the lack of using a saturation site to test everyone in an entire town or city, is that the treatment group continued receiving 83.3% of the conditional benefits as the control group.

The single greatest problem with the design of Finland’s basic income experiment is that the treatment group continued receiving 83.3% of the conditional benefits as the control group.

That fact is extremely important to understand, and it should be considered nothing short of shocking. If the primary goal of the experiment was to see what would happen if people stopped losing benefits in exchange for employment, then the treatment group should have received as close to zero conditional benefits as possible. If you don’t understand why, put yourself in their shoes.

Imagine you are receiving 560 euros per month in basic income (or about $630). Although true that if you accept employment you will get to keep that money where usually you would lose it under typical unemployment benefits, in this experiment, accepting employment would still mean losing the benefits you are receiving for your family, losing your other benefits, and possibly even losing your housing assistance. That’s still a lot of disincentive to work isn’t it?

Finland’s basic income experiment didn’t test the removal of the work disincentive which conditional benefits create. It only slightly reduced them. Again, the experimenters themselves appreciated this. It’s the politicians making the decisions who didn’t. The experimenters hands were tied. How? According the the report itself, it mostly came down to kids…

It is more surprising to note that the amount of the unemployment benefits paid to the treatment group is in fact only about one-fifth smaller than the amount of the benefits paid to the control group. This is a direct consequence of the Act on the basic income experiment, according to which unemployed persons must apply for unemployment benefits just as before if they are entitled to unemployment benefits that are higher than the basic income. In this way, especially families with children who received a basic income were forced to apply for unemployment benefits in order to receive child increases. According to the research group that planned the experiment, the child increases should have been included in the basic income, whereby the basic income would have also been a truly unconditional benefit for families with children. It did not turn out this way, however. This feature of the experiment means that a majority of individuals in the treatment group did not benefit from the lower bureaucracy and the fact that active labor market measures were non-compulsory due to choosing to apply for the standard unemployment benefit.

In other words, it was a political decision in an experiment about replacing unemployment benefits with basic income to require people receiving basic income to continue applying for unemployment benefits, because the size of unemployment benefits varies, especially according to household size.

If politicians had any understanding of the scientific method, they’d have agreed to the scientific recommendation to provide a basic income for kids too, paid to the parent, so that unemployment benefits could be replaced regardless of household size. Anyone looking to experiment with basic income should also appreciate this lesson. Kids should be included. If they aren’t, too many conditions still remain, because existing benefits are designed mostly around families, and we all should appreciate that parents make decisions with their kids in mind. Few parents out there are going to take a job that has the potential of leaving their kids worse off.

Another interesting thing to note, is that the number of conditions remaining in the treatment group would have been even greater, if not for the higher total income that basic income afforded by boosting employment incomes which then disqualified some basic income recipients from some benefits. This by the way is also how UBI could effectively replace many existing benefit programs, by simply lifting people out of qualifying for them anymore, just as if they’d started receiving a paycheck of the same size.

Now that we understand just how little basic income was actually tested in this basic income experiment, we can better appreciate the collected data.

The Preliminary Results

First and foremost, there was no discernible impact on employment, save for a small 2% boost in the self-employed, where the proportion of people with earnings from self-employment went from 42.85% to 43.70%.

Knowing what we know about just how many conditions the basic income group still faced, that makes a lot of sense doesn’t it? There was no observed difference between the treatment group and control group in regards to employment, largely because there’s very little difference between the treatment group and the control group, period. Why would we expect a significant bump in employment, especially within a competitive environment where the unemployment rate is varying between 7%–11%, if people are still largely punished for employment through loss of benefits?

Aside from the typical work disincentives that thus still remained for the basic income group, because this experiment was only provided to 2,000 people, and those people were spread out across Finland instead of being in a town of 2,000 people, there was no boost to demand that would generate new jobs in a true basic income environment.

If all 2,000 people lived in the same town, someone spending their basic income would be someone else’s income, which they in turn would spend, trading hands over and over again, heating up the local economy, and enabling people to find new jobs, offering wages to further increase incomes apart from the basic income, which itself would be spent locally, and would itself circulate, etc. Not only do we already see this through Social Security, the Roosevelt Institute has estimated that through this effect, a UBI would grow GDP in the U.S. by 12.56% in just eight years.

Entrepreneurship too would be further enhanced, because just providing one person cash may function as venture capital and risk reduction for them, but it doesn’t create their customer base. Providing money to everyone is what creates customers, which fuels new businesses. This is why increased entrepreneurship is such a common finding in actual experiments of basic income that impact entire communities. For example, in Namibia’s UBI experiment, entrepreneurship jumped 301%. In India’s UBI experiment, entrepreneurship in treatment villages was observed at three times the rate as control villages. These are the results of both increased capital and increased consumer buying power combined.

Economic stimulation and creation of new jobs would without a doubt exist in any full implementation of actual UBI. So concluding that because more employment wasn’t seen in Finland in one year, that we’ve learned something about a nationally implemented UBI’s effect on employment, is just a bad conclusion.

We do however already know something about UBI’s effects on part-time and full-time employment from a statewide implementation of a small UBI elsewhere — Alaska. Since 1982, Alaska has been distributing around one-fifth of what Finland tested, to all residents of Alaska, regardless of employment. A study evaluating its effects on employment determined a neutral effect on full-time employment, just as in Finland, but with a 17% boost in part-time employment. The boost is a result of a stimulated economy which created more part-time jobs, and that’s with a fraction of the amount Finland tested, which is itself a fraction of a full basic income. If Alaska had first tested its dividend on 2,000 people, I don’t expect they’d have observed a boost in part-time employment either.

Perhaps we should also be asking ourselves if boosting employment is even the point of unconditional basic income, and if not, what is the point? Now that’s a question that the Finland experiment has shined some new additional light on, because employment wasn’t the only thing researchers measured.

In surveying the participants about aspects of their lives other than employment, their answers suggest that basic income reduced their stress levels, increased their senses of physical and mental health and well-being, increased their financial stability, grew their confidence, and even increased their levels of trust in other people and government, including politicians.

Remember that the basic income group really only saw around a 20% reduction in their conditional benefits, so these results should be considered surprising even if the basic income group saw a 100% reduction in the conditions imposed upon them. That these results were seen with a relatively small decrease in bureaucratic conditions, should be considered as nothing short of jaw-dropping. What it seems to suggest is that even just a little bit more freedom, dignity, and security goes a very long way.

Across measure after measure, basic income improved what was measured:

- Life Satisfaction: Those provided with standard benefits in Finland rated their satisfaction with life as a 6.76 on a scale of 0 to 10. Those provided a partial basic income rated their life satisfaction as a 7.32. That’s an 8.28% improvement.

- Trust: Among the unemployed in Finland, trust in others is lower than the population as a whole (possibly because they’re unemployed), but being provided a partial basic income instead of standard benefits increased their trust in other people by 6%, the legal system by 5%, and politicians by 13%. (Note: this supports previous findings)

- Confidence: 58% of those provided partial basic income were strongly or quite strongly confident in their futures, compared to 46% provided standard benefits — a 26% improvement. 42% were strongly or quite strongly confident in their financial situation, compared to 30% — a 40% improvement. 29% were strongly or quite strongly confident in their ability to influence society, compared to 22% — a 32% improvement.

- Physical and Mental Health: 55% of those provided partial basic income considered their physical and mental health to be good or very good, compared to 46% provided standard benefits — a 20% improvement. (Note: this supports previous findings)

- Concentration: 67% of the partial basic income group felt they could concentrate well or very well, compared to 56% on standard benefits — a 20% improvement. (Note: this supports previous findings)

- Depression: A loss of interest in things once considered enjoyable is a key sign of the onset of depression. Among those provided partial basic income, only 25% felt that way during the previous year, compared to 34% of those provided standard benefits — a 36% improvement.

- Financial Security: 39% of those receiving partial basic income felt they were barely getting by or finding it difficult to make ends meet, compared to 49% of those provided standard benefits — a 26% improvement.

- Stress: 55% of the partial basic income group felt little to no stress at all, compared to only 46% of those provided standard benefits — a 20% improvement. (Note: this supports previous findings)

- Attitudes Toward UBI: 68% of those receiving partial basic income strongly agreed that a nationwide UBI would make it easier to accept job offers, compared to 42% of those provided standard benefits — a 62% increase. 51% felt a nationwide UBI would make it easier to start a business in Finland, compared to 39% of those provided standard benefits — a 31% increase. 65% felt Finland should now adopt UBI, compared to 49% provided only standard benefits — a 33% increase.

It’s important to note that all the above results are from 586 people who were successfully interviewed, which is of course a fraction of the 2,000 people. It’s possible that those willing to be interviewed were only those who were happier with the results of being provided partial basic income. It’s also important to note that all of the above is still preliminary data absent the second year of register data.

With that said, there does appear to be across-the-board improvements on a wide range of measures, and all despite the fact that those provided partial basic income still had to deal with bureaucracy and conditions, just a bit less of it.

An entirely fair conclusion to draw from the preliminary results is one that involves flipping around the point of the experiment…

Imagine everyone in Finland already had UBI, and this experiment was looking at if creating new conditions and hiring a team of bureaucrats to apply those conditions would be a good idea. Obviously it isn’t. The results show that those conditions would not increase employment, and would instead have across-the-board negative effects. No one would look at such an experiment as evidence for switching from unconditional basic income to conditional unemployment benefits.

Finally, there is one more important thing to learn from Finland’s experiment with basic income, and that’s what they didn’t even bother to measure, because it’s about us as a society.

The Unmeasured Data

In all of the headlines about the negligible effects on employment observed in Finland’s basic income experiment, one thing goes entirely assumed, that employment is the only way of measuring one’s contribution to society.

No where in the report is the word “volunteering” or “unpaid work” even mentioned. For all we know, hours spent volunteering were increased by 50% and hours spent caring for others increased by 35%. Those are outcomes of more work, not more employment, but is the goal of work to be paid for it? Or is the goal of work to accomplish the work, paid or not?

The experiment showed a small bump in self-employment, where the self-employed actually earned a bit less. That seems to me like a very positive result, to see that people are willing to earn less, to take a risk. Think about the possibilities. What if five years from now, something just one person among Finland’s 2,000 basic income recipients did in 2017 grew into a new billion dollar industry? What if that industry improved the lives of billions of people all over the world? Innovation takes time, often many years, and it only takes one huge success to make many investments well worth it, regardless of how many other investments yielded no fruit. Paul Graham of Y-Combinator refers to this as black swan farming. All it takes is one, just one.

Another popular assumption about employment is that all employment is better than no employment. Finland’s experiment did not break employment down to the granularity of the nature of the work itself. If they had done so, and the results showed that 50 basic income recipients quit their jobs as telemarketers to pursue their doctoral degrees in biotechnology and quantum computing, would that loss of employment reveal a failure of basic income, or its success? Existing research also shows that going from unemployment into a bad job is worse for your mental health than staying unemployed.

We need to start asking some important questions about employment. How much employment actively hurts society? How many people have jobs that are the opposite of contributing to society, and instead drag society down? How many people have entirely unnecessary jobs that don’t need to exist at all? How many people have jobs that could already be done more cheaply and with higher quality and dependability by existing technologies? How many hours are we clocking that could be reduced without accomplishing less?

None of the above questions were investigated in this experiment, because for the most part, these questions aren’t being asked by society in general because of a mass delusion that all employment is good. That assumption is not only wrong, but dangerously wrong with exponential technological advancement.

The BIG Question

So again, we need to ask the question, what is the goal of unconditional basic income? The answer is not job creation. Yes, UBI will likely create jobs due to the economic impact of increasing demand requiring increasing supply, but that’s not it’s purpose. It’s just one of many effects.

To answer the purpose of UBI requires asking another question, and that question is “What is our purpose?” What is our purpose as individuals? What is our purpose as a society? I can only speak for myself, but I believe our purpose is to make life better for everyone. Better is of course subjective, but I think Finland’s experiment did show that compared to the existing system built on distrust, partial basic income made life better for its recipients, by simply trusting them with the agency of making their own decisions. It was a test of freedom, dignity, security, and more, and it adds to the growing pile of evidence that human beings simply thrive more in systems based upon such core principles.

Personally, what’s surprising to me, is how that’s surprising to anyone.

Special thanks to: Haroon Mokhtarzada, Steven Grimm, Andrew Stern, Stephen Starkey, Roy Bahat, Floyd Marinescu, Aaron T Schultz, Larry Cohen, Gisele Huff, Robert Collins, Stephane Boisvert, Justin Walsh, Daragh Ward, Joanna Zarach, Ace Bailey, Albert Wenger, Victor Lau, Peter T Knight, Danielle and Michael Texeira, Jack Canty, Paul Godsmark, Vladimir Baranov, Rachel Perkins, Chris Rauchle, David Ihnen, Michael Hrenka, Natalie Foster, Reid Rusonik, Matt DeKok, Carl Watts, Daniel Brockman, Carrie Mclachlan, Michael Honey, George Scialabba, Che Wagner, Jess Allen, Gerald Huff, Will Ware, Jan Smole, Joe Ballou, Gray Scott, Myi Baril, Max Henrion, Arjun Banker, Chris Smothers, Alvin Miranda, Kai Wong, Jill Weiss, MARK4UBI , Elizabeth Balcar, Georg Baumann, E. Davies, Dylan Taylor, Bryan Herdliska, Mark , Kirk Israel, Valentina Petricciuolo, Elizabeth Corker, Meshack Vee, Kev Roberts, Chris Boraski, Lee, VilliHaukka , Casey L Young, Oliver Bestwalter, Thomas Welsh, Walter Schaerer, all my other funders for their support, and my amazing partner, Katie Smith.

Would you like to see your name here too?

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.