We Gave Homeless People Cash. They Bought Housing Not Drugs.

The evidence from Vancouver to Denver is undeniable: When people in crisis receive money, substance use goes down, employment goes up, and homelessness ends.

On any given night in the United States, over half a million people have no place to call home. They sleep in shelters, in cars, under bridges, and on sidewalks. We spend billions trying to address this crisis through a labyrinth of programs, vouchers, case managers, and bureaucratic systems — and yet the number of people experiencing homelessness has been climbing. What if we’ve been approaching this problem backwards?

In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. offered a different vision:

“We are likely to find that the problems of housing and education, instead of preceding the elimination of poverty, will themselves be affected if poverty is first abolished. The poor transformed into purchasers will do a great deal on their own to alter housing decay.”

King understood something that policymakers have been slow to grasp: poverty is the root, and homelessness is the branch. We’ve spent decades trying to prune the branches while ignoring the roots. But a growing body of rigorous scientific evidence now points to a deceptively simple solution that works far better than our current approaches.

Provide basic income.

Not vouchers. Not services. Not case management alone. Cash. Unconditional cash directly into the hands of people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. And the results aren’t just good — they’re transformative.

A big thanks to my monthly patrons who contribute to making my articles possible and free for all. If you find value in my writing and would like to support it, please join my Patreon or become a paid subscriber here on Substack.

The Vancouver Experiment

In 2018, researchers at the University of British Columbia launched what would become possibly one of the most important studies on homelessness ever conducted. Published in PNAS in 2023, the experiment was elegantly simple: take 50 people who had recently become homeless in Vancouver and give each a one-time cash transfer of $7,500 CAD — roughly 60% of their average annual income — with no strings attached.

The results defied every stereotype about homeless people and money.

Over the following year, cash recipients spent 99 fewer days homeless than the control group. They spent 55 more days in stable housing. They retained $1,160 more in savings. And here’s the finding that should put to rest the most persistent myth about giving cash to the poor: there was no increase in spending on alcohol, drugs, or cigarettes. None. In fact, it dropped by 39%. The money instead went exactly where you’d expect it to go if you stopped thinking of homeless people as fundamentally different from yourself — food, housing, transportation, and durable goods.

Even more remarkable was the cost-effectiveness. The cash transfers generated $8,277 in societal savings through reduced shelter use alone, resulting in a net savings of $777 per person after accounting for the cost of the transfers themselves. We didn’t just help people — we saved money doing it.

The New Leaf Project, as it came to be known, was later expanded to 239 participants and disbursed over $1 million in cash transfers. The expanded results confirmed and strengthened what the pilot suggested: cash recipients spent 40% more nights in stable housing and retained 85% more in savings after 12 months. They even earned 21% more in wages, meaning they worked more and/or found better jobs.

“Across all outcome areas, the data told a consistent story. Unconditional cash support led to rapid, measurable gains in housing stability, financial security, food stability, and key aspects of employment, without reducing labor force participation or increasing irresponsible spending.”

When people have resources to meet their basic needs, to feel stability and hope, they reduce their substance use and secure housing. They stop self-medicating their misery because they have less misery to medicate and start improving their living situations.

What Denver Really Shows

If you’ve followed the debate around cash transfers and homelessness, you may have heard that the Denver Basic Income Project “failed.” This narrative deserves a closer look, because what actually happened in Denver tells a far more interesting and hopeful story.

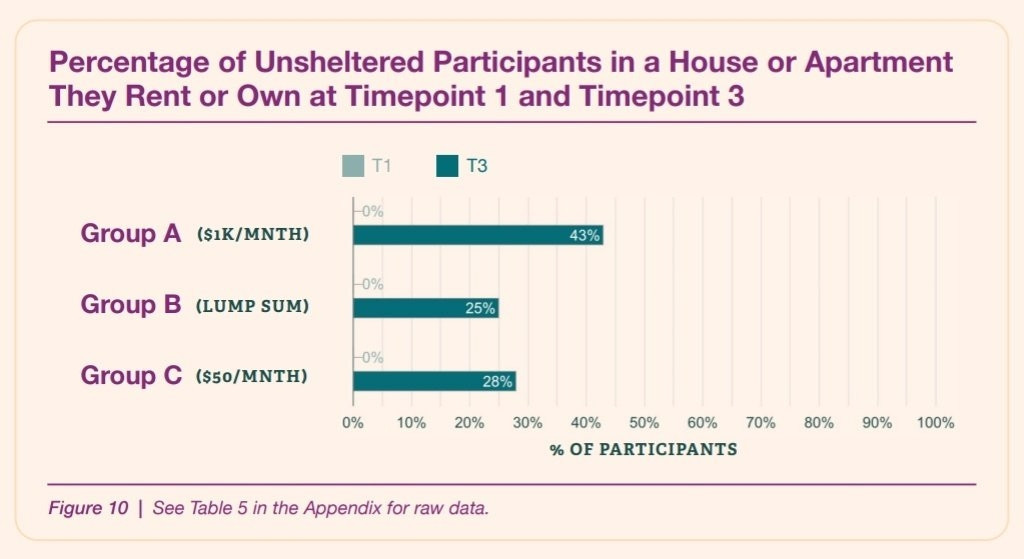

The Denver pilot, launched in 2022, tested three different approaches with people experiencing homelessness. Group A received $1,000 per month for 12 months. Group B received a $6,500 lump sum followed by $500 per month. Group C received just $50 per month. Crucially, all three groups also received something incredibly valuable that often gets overlooked: a free cell phone with a data plan, plus connections to local charities and support services. This matters because in the 21st century, a phone is infrastructure for survival — you can’t apply for jobs, receive callbacks from employers, or stay connected with family who might offer help without one.

Here’s what happened: 43% of those who started unhoused and who got $1,000 a month ended up housed, compared to 25% of the lump sum group and 28% of the $50 group. That’s nearly twice as many people housed in the highest cash group compared to the comparison groups. Full-time employment increased in Groups A and B — from 18% to 23% in the $1,000 group, and from 24% to 37% in the lump sum group. Meanwhile, employment actually decreased in the $50 control group, from 26% to 21%.

Think about that. The group receiving substantial cash saw employment go up. The common fear that giving people money will make them stop working has it exactly backwards. Money doesn’t create dependency — it creates opportunity. It pays for the bus fare to get to a job interview. It covers the work clothes you need for your first day. It keeps your phone on so employers can call you back. It provides the stability needed to hold down a job once you get one.

And what about drug use? This is the fear that dominates every conversation about giving cash to homeless people. Surely they’ll just spend it on drugs, right?

Wrong. The Denver study found no statistically significant increase in substance use across any group. What did change was blood plasma selling — a marker of financial desperation where people literally sell parts of their bodies for cash. Plasma selling dropped by 60% in Groups A and B. But in the $50 control group? It rose by 17%. When people have money, they stop doing desperate things for money.

Numbers don’t capture everything. The qualitative findings revealed that participants in Groups A and B reported decreased stress, increased hopefulness, and reduced anxiety. They started setting long-term goals — housing, school, transportation. Meanwhile, Group C participants could only focus on immediate survival needs like gas, food, and hygiene. When you’re drowning, you can’t think about swimming lessons.

One finding that particularly caught my attention: almost all participants noted feelings of relief when asked about the impact of the program on their daily lives. One participant mentioned how paying for car insurance for the first time made it possible to drive without the constant stress of looking over their shoulder, waiting to get pulled over or get into an accident they couldn’t afford. Another participant noted that cash was fundamentally different from other benefits: “Food stamps, you can only use it on food. Any other benefits, you can only use it on those bills, and oftentimes, you can’t do it, because you’re using cash to pay someone else’s bill because they’re letting you have a place to stay. With DBIP, you can use that cash on anything you want. That makes a huge difference.”

Here’s another important nuance: sometimes what someone experiencing homelessness needs isn’t actually thousands of dollars — it’s fifty. The Denver study included a $50/month group as the control. Qualitative interviews showed that sometimes the barrier to accepting help from friends or family wasn’t the absence of people willing to help, but the shame of not being able to contribute anything. Having even a small amount of money can transform the psychological dynamic of asking for help. “Can I stay with you?” becomes “Can I stay with you? I can help with utilities.” The difference between those two questions can mean the difference between housed and unhoused.

So why do people claim Denver “failed”? Largely because the differences between the treatment and comparison groups weren’t as dramatic as some hoped. But this misses some crucial points: the comparison group wasn’t a true control. Everyone in the study received phones, data plans, and connections to support services. Group C also received more existing welfare support than Groups A and B, whose higher incomes made them ineligible for programs like SSI. When you give the “control” group substantial help too, of course the gap narrows. The real story is that just trusting people with cash worked, and those with more cash improved the most.

Miracle Money and the “Cash Plus” Lesson

Another real-world test of the “give homeless people money” approach comes from Miracle Money: California, a partnership between Miracle Messages and USC researchers. It’s important because it didn’t just test cash—it tested cash plus human connection, pairing monthly payments with a volunteer “phone buddy” (Miracle Friends) designed to rebuild relational support alongside financial stability.

The program scaled up what looked promising in a small earlier pilot. In that initial Miracle Money pilot, 14 people received $500 per month for six months, and among those who were unhoused at entry, 67% secured stable housing.

Then came the larger test. Launched in 2022, the larger study provided 103 unhoused participants in the Bay Area and Los Angeles County with $750 per month for 12 months, distributing nearly $1 million in cash between 2022 and 2024, and tracking outcomes for 15 months across three groups: cash+social support, social support only, and a waitlist control.

Here’s the nuance. Nearly half of the cash group exited homelessness during the study window—48%—but the study did not find a statistically significant difference in homelessness exits compared to the other groups (38% in the social-support-only group and 43% in the waitlist control), meaning researchers couldn’t claim the cash-plus model reduced homelessness in this particular test. That’s not evidence that cash “doesn’t work.” It’s evidence that amounts matter in high-rent environments, and that a payment sized below local housing costs may function more as stabilization and triage than as a housing guarantee.

What Miracle Money did do—decisively—is crush the moral panic. Recipients spent nearly all of the money on basics, because of course they did. In the reporting on the study, the biggest categories were food (26%), housing costs (24%), and transportation (13%). Spending on “temptation goods” (alcohol, cigarettes, drugs) was under 5%, and there was no increase in it. Employment also didn’t drop—again.

And the “plus” mattered. If Denver shows that large enough cash amounts move housing outcomes more, Miracle Money shows something complementary: even when the payment size isn’t enough to buy a clean exit from homelessness in a high rent market, cash still buys breathing room—and breathing room is where better decisions, follow-through, and reconnection become possible.

The Prevention Revolution

Everything I’ve discussed so far has focused on people who are already homeless. But what about keeping people from becoming homeless in the first place? This is where the evidence becomes even more compelling.

In 2016, researchers from the University of Notre Dame published a groundbreaking study in Science that examined what happened when people on the brink of homelessness in Chicago received emergency cash assistance of around $1,000. The results were stunning: recipients were 88% less likely to become homeless within three months and 76% less likely within six months. Even over a two-year period, they remained significantly less likely to ever end up on the street.

This is the prevention insight that changes everything. We currently spend tens of thousands of dollars per person per year keeping homeless people alive — shelters, emergency rooms, jails, social services. New York City alone spends millions putting homeless people up in publicly-funded hotel rooms. What if we invested a fraction of that upstream, before people lost everything?

Oakland’s Keep Oakland Housed initiative has been doing exactly this since 2018, using a points-based system to identify those at highest risk — including foster care youth — and providing $5,400 to $8,150 in assistance. The result? 92% of recipients avoided homelessness six months later. The model is now being deployed across Alameda County.

Consider what universal basic income would mean in this context. It wouldn’t just reduce existing homelessness — it would prevent much of it from ever happening. When everyone has a guaranteed income floor, the cascade of events that leads from a job loss to an eviction to a shelter to the street gets interrupted at the very first step. You don’t need emergency assistance if you never face the emergency in the first place.

Cash Beats Vouchers

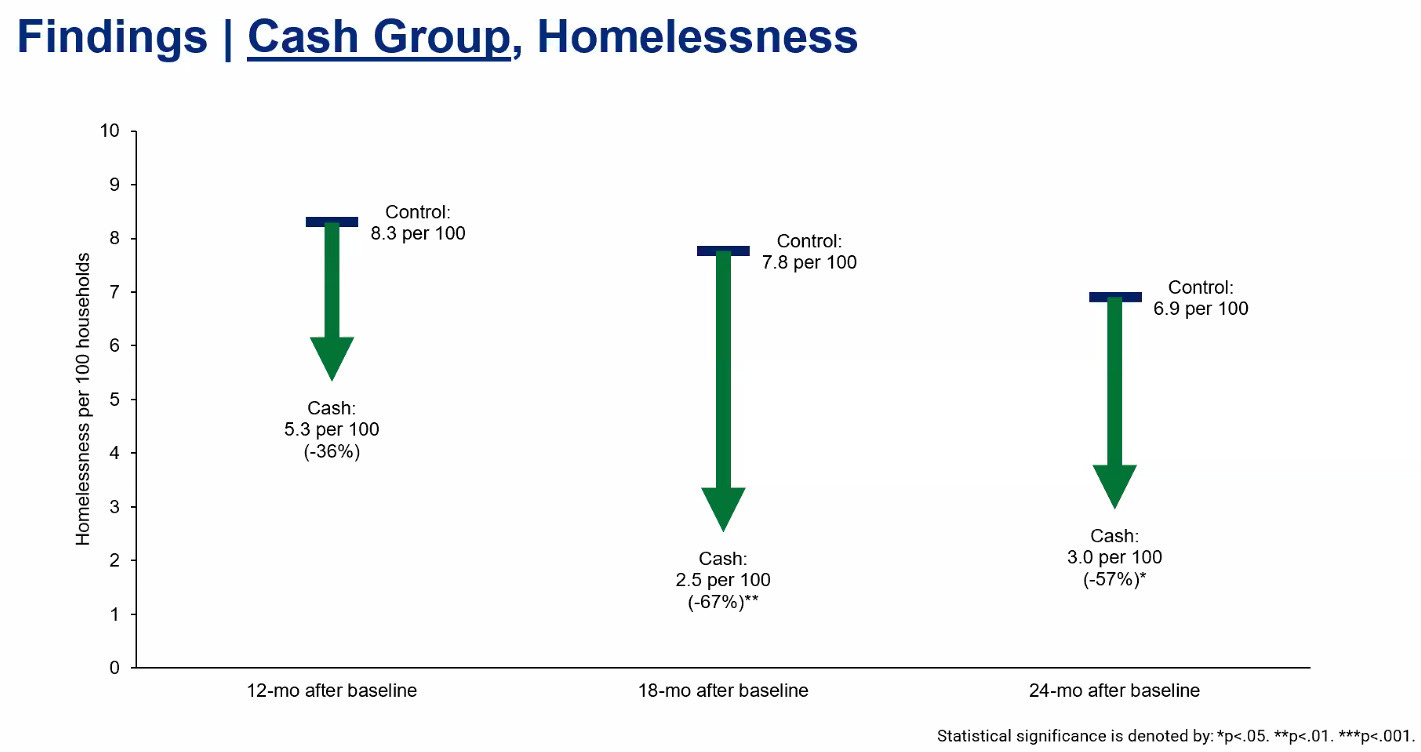

Perhaps the most policy-relevant evidence comes from Philadelphia, where researchers recently conducted a randomized controlled trial directly comparing cash rental assistance to traditional housing vouchers. This is the head-to-head comparison that housing policy has long needed.

The results should reshape how we think about housing assistance.

Cash assistance achieved a 100% utilization rate — every single household was able to use their benefit. Housing vouchers? Only 75% utilization. One in four families offered a voucher couldn’t actually use it, despite Philadelphia having a higher-than-average voucher success rate. The reasons are familiar to anyone who has navigated the housing system: landlords who won’t accept vouchers, bureaucratic delays, housing that doesn’t meet inspection requirements, the sheer complexity of the process.

Cash recipients experienced a 63-75% reduction in forced moves compared to controls. Their rate of homelessness was cut by 67% at 18 months — 2.5 per 100 households versus 7.8 for controls and 6.3 for vouchers. They also reported 22% fewer serious housing quality concerns. Cash worked faster and more completely than vouchers because it gave people the flexibility to solve their own problems in their own ways.

This finding illuminates something fundamental about how we approach poverty. We’ve built elaborate systems designed to help the poor while not trusting them. We create vouchers instead of cash because we worry people will make bad choices. But the evidence consistently shows that people experiencing poverty know what they need. They don’t need us to make decisions for them. They just need resources and the freedom to act with agency and human dignity.

Youth and the Missing Safety Net

One population deserving special attention is homeless youth. Oregon’s Direct Cash Transfer Program provided 117 young people aged 18-24 with $1,000 per month for two years, plus a one-time $3,000 payment. At the program’s end, 91% reported stable housing.

Why does cash seem to work especially well for young people? Research from Merrill Lynch shows that American parents give their adult children approximately $500 billion annually in financial support. This invisible safety net — helping with rent, covering emergencies, co-signing leases, providing a place to crash — isn’t equally distributed. White parents are significantly more likely to provide this support than parents of color, reflecting generations of wealth inequality.

Cash transfers for homeless youth function as a substitute for this inequitable safety net. One participant, Gabi Huffman, used her funds for the mundane necessities that separate housed life from unhoused life: car insurance, gas, work clothes, a laptop for community college. She also paid for her father’s cremation. She moved from a church basement shelter to a duplex with her daughter.

These aren’t stories of young adults becoming dependent. They’re stories of people getting the resources they need to build lives.

Addressing the Rent Question

At this point, a reasonable objection arises: if we give everyone money, won’t landlords just raise rents to capture it all?

This concern deserves a full article of its own, but let me offer several responses.

First, UBI would enable many current renters to become homeowners, which actually increases the supply of rental housing. In the Gary, Indiana pilot in the 1970s, home ownership rates increased by over 30% for pilot participants.

Second, UBI reveals true demand for housing — demand currently distorted by the fact that millions who need homes can’t signal that need in the market. Developers need accurate demand signals to know where to build and how much.

Third, UBI creates an entirely new market for landlords. Currently, renting to low-income tenants is very risky because their income is unstable. But a guaranteed basic income makes everyone a reliable renter with predictable income that landlords can trust.

Fourth, UBI should be accompanied by complementary policies: replacing single-household zoning with multi-household zoning, implementing land value taxes to encourage development and push down rents, and where appropriate, rent controls paired with policies that ensure housing supply keeps growing despite the controls. The solution isn’t to abandon cash transfers — it’s to pair them with policies that ensure housing abundance.

What Saturation Would Show

Here’s something important about every study I’ve described: they were all targeted interventions. Cash went specifically to people experiencing homelessness, not to entire communities. We haven’t yet run a saturation pilot in the US (aside from arguably Chelsea Eats) — giving basic income to everyone in an area — specifically designed to measure effects on homelessness.

But think about what such a pilot would likely show. When everyone in a community has a basic income, local spending increases. One fear is increased rents, but local GDP grows. Local businesses hire more workers. More job opportunities emerge for everyone, including those escaping homelessness. The currently homeless aren’t just receiving cash — they’re participating in a more prosperous local economy with more opportunities to earn additional income.

This is critical: basic income is a floor, not a ceiling. It provides a foundation from which people can build. It doesn’t replace work income — it supplements it. And when that foundation exists for everyone, the entire community benefits.

The Truth About People

What all this evidence reveals is something that should have been obvious to everyone from the start: homeless people are people.

They’re not a separate species with fundamentally different desires or capabilities. They’re not Homo homeless. They’re not uniquely prone to irresponsibility or addiction. They’re people who, through some combination of circumstances — job loss, medical emergency, family breakdown, mental health crisis, addiction, domestic violence, or simply bad luck — found themselves without enough money to keep a roof over their heads. Any of us could find ourselves in similar circumstances. Anything can happen to anyone at any time. It’s Murphy’s Law.

Poverty isn’t punishment for poor choices. It’s a condition that causes poor choices by trapping people in survival mode, unable to think beyond the next meal or the next night’s shelter. The cognitive burden of scarcity consumes mental bandwidth that could otherwise go toward planning, problem-solving, and building a better future. Poverty is a trap, not a verdict. It certainly shouldn’t be akin to a guilty verdict.

This is why the fear that cash will be wasted on drugs gets it backwards. Drug use among homeless populations isn’t caused by having money — it’s caused by not having enough. It’s a coping mechanism for misery, a way to escape unbearable circumstances, a form of self-medication when real medicine isn’t available. Study after study shows that when people receive cash, drug use doesn’t increase. Often it decreases — significantly, as the 39% drop in the New Leaf expansion demonstrates. People stop self-medicating their misery because they have less misery to medicate. They start building futures because they can finally see futures worth building.

Supply people with money and they buy food. They pay for housing. They fix their cars so they can get to work. They buy phones so employers can reach them. They pay for the small things — bus passes, work clothes, car insurance — that make the difference between drowning and swimming. They act, in other words, exactly like you or I would act if we suddenly found ourselves without resources.

The Path Forward

The evidence is now overwhelming and consistent across multiple rigorous studies in multiple cities and countries. Cash transfers reduce homelessness more effectively and more efficiently than our current system of vouchers and services. They prevent homelessness before it starts. They don’t increase drug use — they decrease it. They don’t discourage work — they often increase employment. They save money by reducing the need for emergency services, shelters, and hospitals.

Universal basic income would take these findings and apply them at scale, not just to those who have already fallen through the cracks, but to everyone, ensuring that the cracks themselves disappear. An unconditional basic income floor means that hard times happen less often and anyone facing hard times — anyone at all, because it can happen to any of us — has resources to maintain stability while they get back on their feet and rebuild their lives.

Dr. King was right. Abolish poverty first, and the problems of housing will become far more tractable. Transform the poor into purchasers, and they will do a great deal on their own.

The question is no longer whether cash works. The evidence has answered that decisively. The question is whether we’re ready to trust people — all people — with the resources they need to live with dignity.

The evidence says we should. The evidence says it works.

Period. End of story.

Want more content like this? Please like it, share it with others, and click the free subscribe button. Also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my UBI advocacy work.

Thank you to my UBI Producer level patrons: Gisele Huff, Haroon Mokhtarzada, Steven Grimm, Bob Weishaar, Judith Bliss, Lowell Aronoff, Jessica Chew, Katie Moussouris, David Ruark, Tricia Garrett, A.W.R., Daryl Smith, Larry Cohen, John Steinberger, Philip Rosedale, Liya Brook, Frederick Weber, Dylan Hirsch-Shell, Tom Cooper, Joanna Zarach, Mgmguy, Albert Wenger, Andrew Yang, Peter T Knight, Michael Finney, David Ihnen, Steve Roth, Miki Phagan, Walter Schaerer, Elizabeth Corker, Albert Daniel Brockman, Joe Ballou, Arjun Banker, Tommy Caruso, Felix Ling, Jocelyn Hockings, Mark Donovan, Jason Clark, Chuck Cordes, Mark Broadgate, Leslie Kausch, Juro Antal, centuryfalcon64, Deanna McHugh, Stephen Castro-Starkey, David Allen, Liz, and all my other monthly patrons for their support.

Looking for a UBI-focused nonprofit charity to donate to? Consider donating to the Income To Support All Foundation to support ambitious UBI projects focused on research, storytelling, and implementation to realize economic freedom for all.

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.