The 200-Year Experiment: How a 'Privileged' Basic Income in Brazil Proves We Can Afford to Be Universal

From $500 to $15,000 a Month: How Decades of Data Prove That an Unconditional Basic Income Guarantee Fuels Ambition Instead of Laziness

What if I told you that the Portuguese Empire accidentally ran one of the most comprehensive basic income experiments in human history?

Not a one-year or two-year or even three-year pilot. Not a few hundred or few thousand participants. A policy spanning over two centuries, distributing everything from poverty-level incomes to amounts equivalent to $15,000 per month in modern purchasing power. And the results absolutely demolish the idea that giving people money makes most of them stop working for more money.

This is the question that haunts every conversation about Universal Basic Income. It doesn’t matter if we’re discussing a UBI of $1,000 a year or $10,000 a month or anything in between—someone always asks: “But won’t people just quit their jobs?”

The Brazil data, analyzed in 2025 by Marcelo Ferreira at Princeton, doesn’t just challenge the laziness myth. It drives a stake through its heart. And when we combine this historical evidence with the massive systematic reviews of the past decade and the just-released 2025 End of Year Report covering 27 American pilots, the picture becomes undeniable.

We have been terrified of a bogeyman. Unconditional basic income is the foundation of work, not the enemy of it.

The Daughters of the Empire

To understand why this Brazil data is so remarkable, we need to go back to 1795.

The Portuguese Empire wanted to ensure that families of naval officers wouldn’t starve if the male breadwinner died. The solution was elegantly simple: a pension for unmarried daughters that would last for life. The logic was paternalistic but practical—women had limited economic opportunities in the 18th century, so the state would provide a floor for them to stand on.

But something striking happened as the centuries rolled on. In Brazil, this policy expanded. According to Ferreira’s research, the scope grew through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries even as women’s labor force participation increased and alternative social protections developed. The central legal framework became Law 3765, enacted in 1960, which regulated pension payments to widows and daughters of military personnel. This was essentially when the basic income quasi-experiment started. Prior to 1960, the money was conditional. A reform in 2000 restricted new eligibility to service members who joined before December 28, 2000, but for those already covered, the pensions continued with a small fee.

These laws created a very large cohort with decades of data to analyze. For the purposes of the Ferreira study, it was like looking at an experiment with over 30,000 people in it who got basic income from 2002 to 2025. The “start date” of 2002 is because the full names required to link individuals across different datasets were only provided by the Ministry of Labor starting in 2002.

This wasn’t a means-tested welfare check that disappeared if they got a job. It wasn’t a conditional stipend requiring bureaucratic hoops. It was, effectively, a lifelong guaranteed income for a specific demographic. I reached out to the study’s author, Marcelo Ferreira, to clarify some details about how it worked. “It is not conditional,” he confirmed, pointing to official Brazilian Navy guidelines. In 2001, military personnel could opt to contribute 1.5% of their pay to keep their daughters covered under the old rules. “I don’t have data on this decision,” Ferreira told me, “but 1.5% seems like a low fee for getting your daughter covered for life so I would expect that most of them took it.”

Here’s where it gets fascinating. Because military ranks vary wildly, the pension amounts varied wildly too. Some daughters received amounts equivalent to minimum wage. Others received sums tied to high-ranking officer salaries—upwards of $15,000 every month.

This allows us to answer a question that no modern UBI pilot has been able to touch: What happens to people’s motivation to work when a basic income floor is lifelong and enormous?

Conventional economic wisdom—the kind that assumes humans are just mice waiting for pellets—suggests that labor force participation should collapse once the income is high enough to live comfortably. If you’re receiving $10,000 a month for breathing, why would you ever clock in, right?

The answer from the Brazil data may shock you: The impact was small and flattened out over time regardless of size!

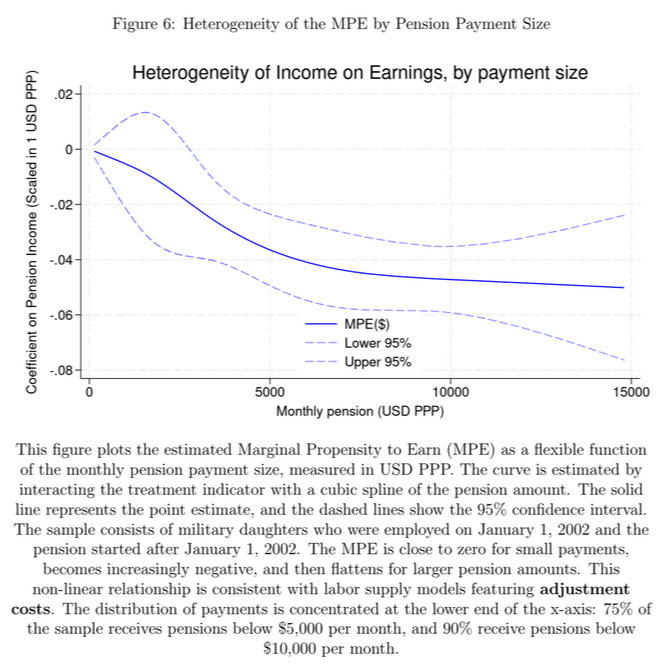

According to Ferreira’s analysis, the income elasticity of labor supply was extremely low. In plain English, that means even as the guaranteed income got bigger and bigger, the decision to work barely budged. When I asked Ferreira what lessons we could draw, he emphasized that the findings extend beyond UBI specifically: “Any social transfers have an element of income effect on labor supply, and it seems like 5 to 10 cents per dollar is a reasonable estimate for how much ‘free cash’ depresses earnings.”

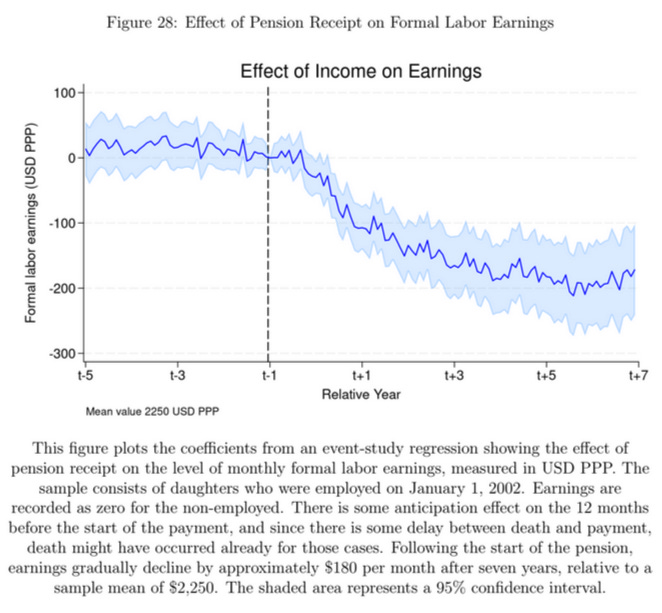

Eight cents per dollar to be exact. That was the "labor cost" of providing total financial security. In a study of permanent, lifetime pensions as high as nearly triple the national median earnings, it was found that for every dollar given, labor earnings fell by just 8 cents. It wasn't the total abandonment of work that critics fear; it was a modest, gradual adjustment—even when the amount of money was life-changing and far higher than any basic income would likely ever be.

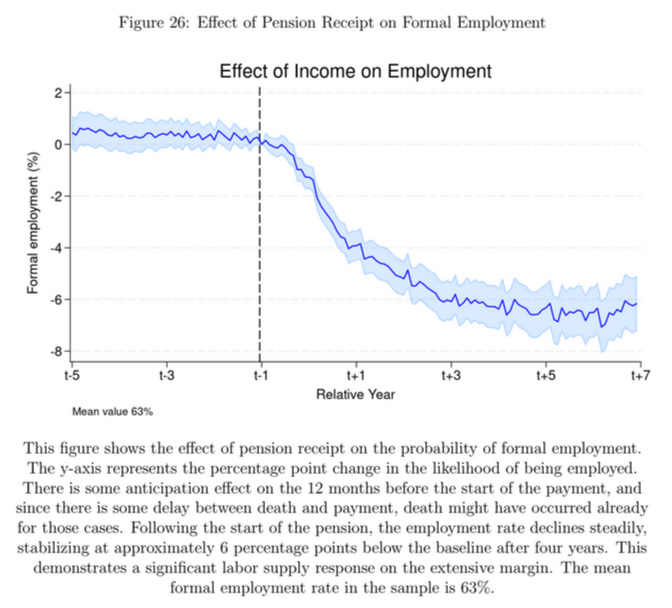

But here’s what makes Ferreira’s findings even more revealing: when he decomposed the labor supply response, he found that “this transfer induces a 10% decrease on the extensive margin of labor supply after seven years, with no effect on the intensive margin.” Translation: the reduction came entirely from some women either dropping out of the workforce immediately or taking longer between jobs. People who continued working didn’t really reduce their hours at all.

The adjustment happened gradually, “driven by a large temporary increase in the hazard of separation and a persistent moderate reduction in the job finding rate.” In other words, some women used the financial security to leave jobs they didn’t want, and others took more time searching for employment that suited them. They weren’t lounging on beaches—they were being selective or doing unpaid work. And those who stayed employed? They kept working exactly as much as before.

This distinction matters enormously. The reduction wasn’t coming from millions of workers each shaving days off their weeks. It was concentrated among those who chose to exit entirely—often older daughters approaching retirement age, or those who could finally afford to leave jobs that made them miserable.

Think about what this all means. We aren’t talking about a small one-time payment. We’re talking about life-changing, “you never have to work again” money. And yet these women participated in the labor force at remarkably high rates. In many cases, their participation rates exceeded the general population because they had the resources to secure education and childcare.

Tragically, this golden natural experiment may be nearing its end. In October 2025, a bill was introduced in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies—PL 1.160/2025—that would make these pensions conditional on remaining unmarried. If passed into law, if the daughters marry or form a civil union, they would lose the benefit entirely. It’s the typical policy instinct: means-test everything, add conditions, ensure that no one is getting something they don’t “deserve” or “need.”

But for now, those covered under the old rules continue to receive their unconditional income. The Brazilian Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled in favor of the daughters when challenges arise. And the data we’ve gathered from decades of this policy remains some of the most powerful evidence we have about human behavior under conditions of permanent, real, financial security.

Defining What We’re Actually Talking About

Before we go further, let’s be precise about what Universal Basic Income actually means, because the term gets thrown around carelessly.

UBI is defined as a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement. It is cash with four additional characteristics: universality, unconditionality, regularity, and individuality.

Everyone gets it, regardless of employment status or wealth. No strings attached—you don’t have to prove you’re looking for work or attending job training and you don’t lose it as a result of accepting a job. It comes reliably, typically monthly, not as a one-time windfall. And it goes directly to individuals, not household heads who may or may not distribute it fairly.

The Brazil pensions were periodic, unconditional cash payments to individuals. And because they lasted for life, they removed the “duration bias” that critics often cite regarding short-term pilots. These women knew the money was never going away. They had every rational incentive to be lazy. And they chose to be productive instead.

Remind you of any millionaires or billionaires who can entirely afford to stop working and don’t?

The Scientific Consensus: It’s Not Just Brazil

If the Brazil study were the only data point, you could perhaps argue it was a cultural fluke, an artifact of a specific time and place. But it’s not. It’s just the most dramatic example of a trend that appears in virtually every rigorous study of unconditional cash.

In 2018, Gilbert and colleagues published a massive systematic review in the peer-reviewed journal Basic Income Studies. The researchers analyzed 16 major basic income trial programs involving over 105,000 people across 12 nations.

The results? 93% percent of reported outcomes showed no meaningful reduction in work when the criterion was set at a 5% decrease or more.

When the researchers looked at the numbers, the laziness argument was statistically nonexistent. In the vast majority of cases, the needle simply didn’t move. Even more interesting was what happened in developing economies, where guaranteed income often led to an increase in work.

Why would free money make people work more? Because it takes money to make money. Basic income acts like venture capital for regular people. It buys the tools. It pays for the bus fare to the job interview. It provides the stability needed to take a risk on a better opportunity. And a small amount of money does not make earning more money pointless.

This was further reinforced by de Paz-Báñez and colleagues in their peer-reviewed 2020 systematic review published in Sustainability. After screening over 1,200 documents on the UBI/employment relationship, they selected 50 empirical cases and 38 studies with contrasted empirical evidence. Their conclusion was unequivocal: “Despite a detailed search, we have not found any evidence of a significant reduction in labor supply.”

Instead, they found “evidence that labor supply increases globally among adults, men and women, young and old.” The only groups that consistently worked less were children, the elderly, the sick, those with disabilities, women with young children, and young people who continued studying. As the researchers noted, “These reductions do not reduce the overall supply since it is largely offset by increased supply from other members of the community.”

The 2025 Reality Check: Zero Decline

If historical data and international reviews aren’t enough, look at what just happened in the United States.

The End of Year Report 2025 from Mayors, Counties, and Legislators for a Guaranteed Income represents the largest body of research on this topic ever assembled in America. It covers 27 finalized pilots that have disbursed over $335 million to roughly 30,000 Americans.

The report’s findings on employment are unequivocal. Out of 27 scientifically rigorous studies, how many showed a decline in employment?

Zero.

In 27 different locations, with different demographics and local economies, and with the standard amount of guaranteed income being $500 a month, not a single pilot resulted in people significantly quitting the workforce. Recipients were actually more likely to find long-term employment.

The specific outcomes are striking. In Ithaca, caregivers increased their rate of full-time employment. In Baltimore, parents missed 9 fewer hours of work per month due to childcare challenges. In Santa Fe, students used the money to finish school.

This is the reality of human psychology. People aren’t quitting en masse because they start each month with $500 to $1,000. They’re keeping their jobs because that check fixes the car that gets them there and they want far more than $1,000 a month.

The ORUS Elephant: Let’s Actually Look at the Numbers

So how do we square all this evidence—the Brazil history, the systematic reviews, the 27 successful pilot studies—with headlines about the OpenResearch study showing a “significant” reduction in work?

Let’s actually look at what those numbers mean.

According to the ORUS researchers themselves, the reduction in work hours represented an “approximately 4%-5% decline relative to the control group mean.” Remember the Gilbert systematic review that found 93% of trials showed no meaningful reduction? Their criterion for “meaningful” was 5% or more. The ORUS result sits right at or below that threshold—and that’s the average across all participants, including groups we’d expect to work less.

When you break it down further, there were no significant decreases in employment or hours worked among childless adults or those over age 30. The reduction was concentrated entirely among single parents—who shifted to unpaid caregiving—and young adults, many of whom pursued education. For everyone else? Zero percent. The “4%” average is being dragged up by people doing exactly what we’d hope they’d do with financial security: caring for their kids and investing in their futures.

A 1.3-hour reduction per week works out to about 15 minutes less work per day in a five-day workweek. Fifteen minutes. That’s an extra bathroom break. That’s a slightly longer lunch. On an annual basis, it’s equivalent to about 8 days less work per year.

Now here’s some context that should make anyone worried about that number feel a bit ridiculous: Japan has the least amount of paid vacation days of any developed nation in the world, and their legal minimum is 10 days per year. The United States is the only OECD country with zero legally mandated paid vacation days.

So even if we take the ORUS findings at face value and assume that $1,000 of basic income universally causes people to work 8 fewer days per year, Americans would still have less time off than Japanese workers. The difference between us and France would shrink from 30 days to 22 days. Does 8 days of additional rest per year sound like economic collapse to you?

But even that framing is misleading, because the ORUS study couldn’t measure what it couldn’t test.

The ORUS study was a micro-experiment. It gave basic income to a thousand people scattered across Texas and Illinois. It measured the labor supply of those individuals, but it couldn’t measure the labor demand that a true UBI would create.

In a genuine Universal Basic Income scenario, everyone gets the money (but not everyone gets a boost after taxes). That means most (but not all) people are spending additional money. That spending circulates through the economy, driving up demand for goods and services. When demand increases, businesses need to hire more people.

This isn’t theoretical. We see it in Alaska every year. The Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend—where every resident gets an annual payment from oil revenues—had no effect on full-time employment overall. Any reduction was counteracted by spending creating new jobs. There was, however, a 17% increase in part-time employment.

The ORUS study couldn’t capture this multiplier effect because the recipients were too few and too scattered to shift local economies. It measured supply without measuring the demand that universality would generate.

And even setting aside the macro effects entirely, look at who was actually working less in the ORUS data. Again, there were no significant decreases in employment among childless adults or those over age 30. The reduction was concentrated among single parents—who shifted from paid employment to the unpaid (but essential) labor of caring for their children—and young adults, many of whom reduced hours to pursue education.

This isn’t laziness. This is investment. And it’s also freedom.

What Are We Even Doing Here?

There’s one final piece of context that makes the entire “work reduction” panic borderline absurd: artificial intelligence.

We are standing on the edge of the greatest transformation of labor in human history. AI is already handling vast amounts of cognitive and creative work. Entry-level jobs are disappearing. College graduates are finding it harder to get their foot in the door.

In a world where AI and automation are rapidly displacing jobs, why are we so terrified of humans working slightly less? And what does that say about real freedom?

If UBI causes a small reduction in work hours—as people choose to spend more time with their families or pursue education—that’s actually a good thing in an AI-driven future. It means we’re sharing the remaining necessary labor more equitably.

The more work AI does for us, the less sense it makes to hyperventilate about labor supply. We’re solving the problem of production. We have the goods. We have the services. The problem now is distribution. That problem has existed and worsened for 50 years now. We must better distribute growing prosperity.

In an environment where there may not be enough jobs for everyone who wants one, people choosing to work less would actually open up opportunities for those who want jobs. Imagine a work environment where everyone there truly wants to be there and no one feels forced to be there? Imagine that level of freedom from coercion.

The Floor, Not the Ceiling

The lesson from the Brazilian military daughters spans cannot be ignored. They were given a guarantee: “You will survive. No matter what happens, you will have enough.”

They didn’t decay. They didn’t rot. They didn’t retreat from the world. They lived full, active lives. And as the pension grew larger—even up to that $15,000 monthly equivalent—they simply used that security to make better choices.

The systematic reviews covering dozens of trials and hundreds of thousands of people confirm it. The 27 American pilots confirm it. Alaska’s 40+ years of UBI confirms it.

If we implement a UBI and index it to GDP growth, so that as our automated economy gets richer the payment grows with it, the data suggests we have nothing to fear. People want to contribute. They want purpose and meaning.

Ferreira also ran the numbers using a statistics model and concluded that "the redistributive gains from a UBI in Brazil would outweigh its efficiency costs, resulting in net welfare gains." The 5-to-10-cent reduction in earnings per dollar transferred simply doesn't come close to offsetting the benefits of economic freedom for all.

The idea that humans will receive UBI and do nothing but sit on the couch eating potato chips is a cynical myth that has been demolished by centuries of history, multiple comprehensive systematic reviews analyzing over 50 empirical cases, and 27 modern American experimental studies.

UBI is not a ceiling that holds us down. It is a floor. And when you give human beings a solid floor to stand on, they don’t lie down.

They reach for the stars.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it and click the subscribe button. Also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my work to have your name appear below.

Special thanks to my monthly patrons: Gisele Huff, Haroon Mokhtarzada, Steven Grimm, Bob Weishaar, Judith Bliss, Lowell Aronoff, Jessica Chew, Katie Moussouris, David Ruark, Tricia Garrett, A.W.R., Daryl Smith, Larry Cohen, John Steinberger, Philip Rosedale, Liya Brook, Frederick Weber, Dylan Hirsch-Shell, Tom Cooper, Joanna Zarach, Mgmguy, Albert Wenger, Andrew Yang, Peter T Knight, Michael Finney, David Ihnen, Steve Roth, Miki Phagan, Walter Schaerer, Elizabeth Corker, Albert Daniel Brockman, Joe Ballou, Arjun Banker, Tommy Caruso, Felix Ling, Jocelyn Hockings, Mark Donovan, Jason Clark, Chuck Cordes, Mark Broadgate, Leslie Kausch, Juro Antal, centuryfalcon64, Deanna McHugh, Stephen Castro-Starkey, David Allen, Liz, and all my other monthly patrons for their support.

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.