Our Paradoxical Economy Courtesy of Technology and the Lack of Basic Income

The Question of Slowing Productivity Amidst Rising Automation

The latest numbers are in, and there are now more people not working in the U.S. as a percentage of the total population, than ever in the last 38 years. Some are already asking if this may very well be the “new normal” here in the 21st century.

The percentage of Americans in the workforce — defined as those who either have a job or are actively seeking one — dropped to 62.6 percent, a 38-year low, from 62.9 percent… The share of Americans in the workforce had been steadily climbing through early 2000, and a big reason was that more women began working. But that influx plateaued in the late 1990s and has drifted downward since.

The Fall of Human Labor

The above linked report goes on to point to retiring seniors and the youth staying in school as major reasons for the dropping labor force participation rate.

I’ve referred previously to the job market as a game of musical chairs. This game doesn’t have enough chairs for everyone to find a seat. Now, if Baby Boomers are getting up out of chairs, and Millennials are opting not to sit down in them, then why aren’t there a bunch of empty chairs?

Because hardware and software are both now sitting in those chairs.

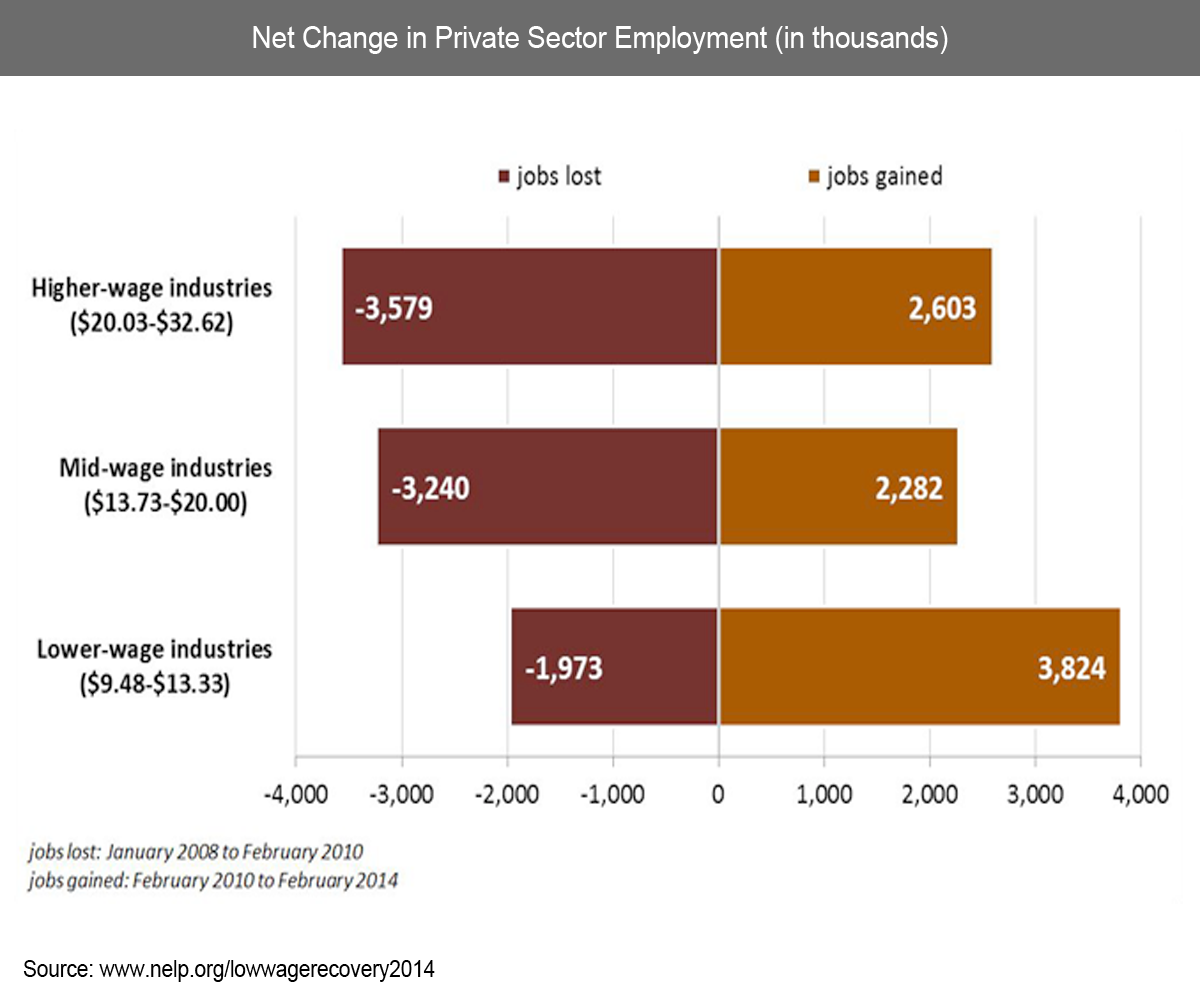

“Job creators” were taught an important lesson after the Great Recession: human labor is no longer needed to the degree it once was. Huge numbers of people were fired from their jobs, and those employers only became more profitable. The entire purpose of technology is to allow us to do more with less, and that’s exactly what it’s doing.

The Rise of Productivity and a Paradox

It should be apparent in looking at productivity, that although growing, it appears to be growing more slowly. How can this be the case if more and more people aren’t working and more and more technology is? This question actually has its own name. It’s called the “productivity paradox” , and it is perplexing more than a few very smart and knowledgeable people.

I believe the confusion rests in how we measure our productivity. Productivity is commonly calculated as GDP divided by total hours worked. When GDP grows or hours go down, productivity goes up. When GDP falls or hours go up, productivity goes down. So what’s going on right now? The answer is something somewhat nonsensical.

Technology has paradoxically begun requiring more hours.

The combined effects of technology and the globalization enabled by it are eating jobs, but for those left working — because they are by and large earning less — they actually need to work more. Instead of jobs requiring the 5–6 hours of work a day they actually on average now require instead of 8, we clock in more than 8 hours as a matter of survival. Instead of working one full-time job 40 hours a week, we work one full-time job 47 hours a week to make sure to keep it, or multiple part-time jobs even more than 50 hours per week to compensate for the lower pay.

What’s going on here is something those like Marc Andreessen seemingly choose to ignore, when they say that although technology is eliminating jobs, it’s also creating new ones, and because prices are going down, everyone is better off.

We are indeed creating new jobs, but these jobs are not 1:1 replacements. When someone who graduated from a free high school loses a 40 hours per week manufacturing job with benefits they’ve worked for 20 years that paid $50,000 per year because technology has eliminated the need for a human to fill that role, and the only job they can find without taking out a second mortgage to go back to school is a 30 hours per week temp job without benefits in the service industry that pays $20,000 per year if they’re lucky, they’ve indeed gone from one job to another, but are they better off? Is the consumer economy better off with the notable hit to consumer spending power? Does the fact that robotic manufacturing allows this person to buy a dishwasher for $500 instead of $700 counteract the $30,000 loss in salary and security? Does the ability to purchase an iPhone 6 for the same price they paid for an iPhone 3 a few years ago make up for that loss in income either?

Advancing technology is not being allowed to improve our lives to the degree it could, if we were to make other decisions as a society. Instead, we’re actively forcing ourselves to work a greater number of hours thanks to the effectiveness of the tools we created to require fewer hours. Does this outcome make any real sense? Is all this new and extra work in the labor market truly necessary or are we performing it because a job, however unnecessary is currently necessary to live?

We’re also increasingly disengaged from all this new and extra (and sometimes entirely pointless) work we’re forced to do, and it’s carrying a large productivity cost as well.

According to a report from Gallup 70% of American workers are either not-engaged or actively disengaged, which means they’re disruptive and undermining workplace productivity. And here’s a related stat: “Gallup estimates that actively disengaged employees cost the US $450 billion to $550 billion in lost productivity per year.”

When we invent work that doesn’t need to exist at all, productivity suffers. When we pay people less per hour, forcing them to work more total hours, productivity suffers. When we feel forced to do work thanks to the inability to decline it, productivity suffers. Just simply having the option to decline a task has been shown to boost productivity by 40%.

We also need to consider how much productivity would increase if the people who didn’t want their jobs were replaced by those who do. Right now there are people who really want specific jobs but can’t get them because they’re not available and instead performed by those who hate them. We could instead create the situation where all those who want specific jobs have them, and those who don’t want them, don’t have them.

At the same time we’re fully voluntarily creating incredible world-changing value in our free time. Creations like Wikipedia and open-source code are not being counted as part of GDP calculations, meaning productivity is rising invisibly. The numbers aren’t showing it because we’re not even counting it.

Our BIG Choice

We all know how the saying goes about giving someone a fish and teaching someone to fish. But what happens when we build a robot to fish? Do we all starve or do we all eat? Well, right now the robots we’ve built to fish are feeding an extremely small percentage of people more fish than they could ever possibly eat, while reducing the ability of everyone else to find any fish at all. This predicament requires some questioning. Is it what we want?

We need to step back and look at the big picture. Our technology has reached the point that it is now partially pulling our economy down instead of fully propelling it forward. Jobs being filled by technological labor should be something to celebrate, freeing us to pursue the kind of work and the number of hours we wish to pursue. But it’s hard to celebrate when we are instead left decreasingly able to earn incomes, and subsequently unable to purchase goods and services as consumers. Remember, our economy is nearly 70% a consumer economy. What we spend is what others earn. So when we can’t earn, we can’t spend, and the economy contracts. Everyone is worse off. When capital replaces labor, inequality increases, and the economy contracts. Again, everyone is worse off.

Technology is providing an increasing abundance of goods and services, while simultaneously preventing people from being able to purchase them. It’s also increasing the number of unemployed while increasing the hours of those left employed. It’s kind of a Gordian Knot isn’t it?

So what do we do?

We have to fundamentally sever the connection between work and income.

If technology has reached the point where hardware and software are together doing much of our work for us, then we have to pay each other what our technology is not earning as income and not spending into the economy as a consumer. We have to give it to ourselves and spend it ourselves, because our technology is not going to. This can be thought of as a technological dividend required to upshift our economy instead of letting it slowly grind to a halt, and it’s more widely known as the idea of basic income.

We need to make sure everyone starts earning a non-work related income so that everyone can be consumers in an economy increasingly populated by non-consuming non-human labor. By doing this, we will also be transforming all work into voluntary work, and see all the effects this makes possible from the economic growth of increased engagement to the higher wages of increased individual bargaining power.

If we take that path, the basic income path, then we can automate even more labor away and grow the basic income even further as productivity reaches new heights.

If we don’t take that path, and continue along the path we’re on, we’re going to continue reading increasingly worse news of the “new normal”, and be led to believe it’s actually normal.

To quote Martin Wolf writing about this collective decision we face in light of advancing technology:

… the ultimate result might be a tiny minority of huge winners and a vast number of losers. But such an outcome would be a choice, not a destiny. Techno-feudalism is unnecessary. Above all, technology itself does not dictate the outcomes. Economic and political institutions do. If the ones we have do not give the results we want, we will need to change them.

Nothing about the way our economy works is “normal” or “natural”. It’s all a bunch of choices, and we can make different ones. We’re the ones making the rules, and it’s time for a new rule. Instead of all starting the month at zero dollars, we can all start at greater than zero. It’s a minor rule change, but a profound improvement to our entire system.

What are we waiting for?

Special thanks to Arjun Banker, Topher Hunt, Keith Davis, Mark Witham, Albert Wenger, Larry Cohen, Joshua Grant, Chris Smothers, Danielle Texeira, Paul Wicks, Liane Gale, Jan Smole, Joe Esposito, Jack Wagner, Richard Just, Stuart Matthews, Natalie Foster, Brad Sorensen, Chris McCoy, Michael Honey, Daniel Brockman, Gary Aranovich, Kai Wong, Peter, Robert F. Greene, Martin Jordo, Victor Lau, Shane Gordon, Paolo Narciso, Johan Grahn, Tony DeStefano, Andrew Henderson, Erhan Altay, Bryan Herdliska, Stephane Boisvert, Rise & Shine PAC, Kirk Israel, Luke Sampson, all my other funders for their support, and my amazing partner, Katie Smith.

Would you like to see your name here too?

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.