What We Can Learn About Systems from W. Edwards Deming

Japan arose like a phoenix from the ruins of World War II to quickly become the second most powerful economy in the world. This unbelievable feat has been called an “economic miracle.”

Do you know how they did it?

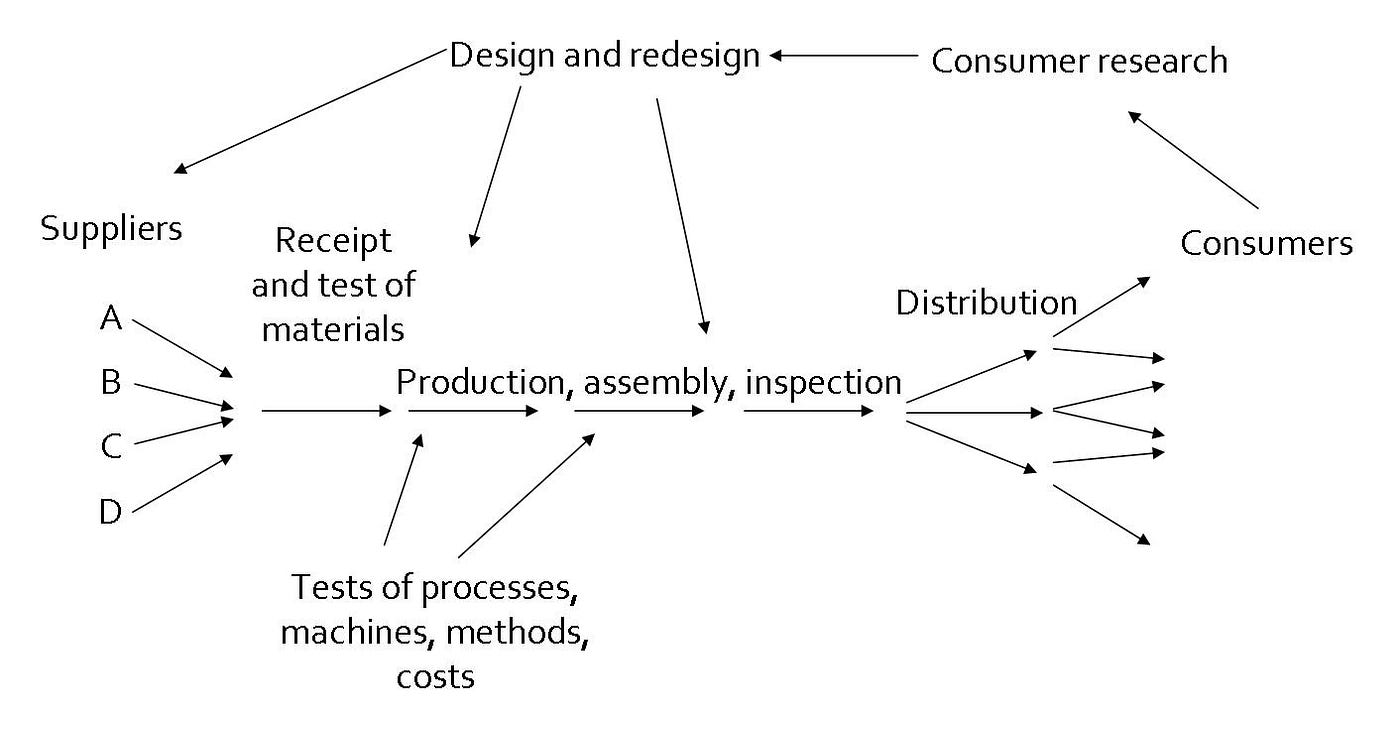

The answer to this question may surprise you. It involves a single American name and a single visualization. The name is W. Edwards Deming. The image is this flowchart:

“Production viewed as a system” — W. Edwards Deming

The Lessons of W. Edwards Deming

In The New Economics, Deming describes how this chart was on the blackboard of every conference with top management in Japan in 1950 and onward, and was seen by 80% of all owners of capital. It was used to teach their engineers. It was used to inform every part of the system of their roles in it.

Deming Lesson #1: Systems

Can you see how this one simple flowchart could be so miraculously transformative?

It’s a circle.

More than that, it’s an interconnected feedback loop designed for continual improvement. The aim of the entire production cycle is always increasing quality. Never stop improving. Never stop innovating. Never stop learning. Never stagnate. Never accept the status quo. Always do better.

It begins and ends with ideas. Without ideas, there can be no improvements.

It begins and ends with suppliers. Without raw materials, there can be nothing produced.

It begins and ends with production. Without production, there can be nothing to distribute.

And most important of all, it begins and ends with consumers.

The consumer is the most important part of the production line. Quality should be aimed at the needs of the consumer, present and future. — W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis

Without consumers, there can be no system. Without listening to the consumer, there can be no improvements. Without being able to hear the consumer through their dollars, a system is destroyed. A system where consumers don’t exist or have no ability to consume, is truly pointless.

As a whole, production seen as a cycle reveals interdependence. Every part of the loop is a part of the system, and every part works together with every other part for the benefit of the entire system that never stops improving.

How exactly did Deming define a system?

A system is a network of interdependent components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system. A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system. The aim of the system must be clear to everyone in the system. The aim must include plans for the future. A system must be managed. It will not manage itself. Left to themselves, components become selfish, competitive, independent profit centers, and thus destroy the system. — W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics

The year is 2015. Our markets are globalized. Our technology is advancing exponentially. Our production is increasingly automated. We have come a long way, but is our economy managed like a system? Is our government? Are we working together? What is our aim? Do we even have one? What is our plan for the future?

Are we even asking these questions?

Deming Lesson #2: Variation

“Follow the man, not the dog.” — Neil deGrasse Tyson

Deming considered knowledge of variation key to management of systems, and so in possibly the most important demonstration ever devised, he taught his students the unavoidable reality of random variation.

In his seminars, he would bring boxes of colored beads and a paddle. For every 400 white beads, there were 100 red beads, and people would be given the job of using the paddle to capture the beads 50 at a time. All results were recorded. The goal with each swipe of paddle through beads, was to get as few red beads as possible. This was known as the “Red Bead Experiment.”

Those who scooped up the most red beads were seen as doing a poor job. Those who scooped up the most white beads were seen as doing a good job. Too many red beads, and one would be punished. Mostly white beads, and one would be rewarded.

It should be clear that no matter what anyone did, there would always be red beads drawn, because red beads were part of the system. They would only randomly vary in quantity. Because red beads were built into the system, those taking part in the experiment were rewarded or punished based purely on natural random variation. No amount of reward or punishment would alter the 4:1 ratio of white beads to red beads. This ratio was set by Deming before the lesson even began. The rest was luck.

Without understanding systemic variation, aside from the futility of reward and punishment, we also make two common and extremely costly mistakes:

Mistake 1: To react to an outcome as if it came from a special cause, when actually it came from common causes of variation.

Mistake 2: To treat an outcome as if it came from common causes of variation, when actually it came from a special cause. [The New Economics]

Imagine firing one employee and handing a bonus to another, without knowing neither act will result in any difference. This is Mistake 1.

Imagine getting sick and thinking it’s the flu without realizing you just experienced food poisoning. This is Mistake 2.

Recognizing and avoiding these mistakes is vital to systemic improvement.

Deming Lesson #3: Knowledge

Nothing can be improved without knowledge. The existence of a hammer does nothing for a human being without understanding how to use it. Facts are just facts. Data is just data. Information is just information. It’s the questions behind our observations that create knowledge through theory. This is how the scientific method works. Noticing that an apple falls is just data. Wondering why it falls, is what leads to formulating the laws of gravity.

A system can not be improved without the application of knowledge through theory. If we learn something new, and don’t apply this new knowledge, our systems can’t change for the better.

To improve a system we must ask questions, develop theories, test the theories, and apply the theories. This is how systems may be continually improved —** scientific thinking.**

At the heart of science is an essential balance between two seemingly contradictory attitudes — an openness to new ideas, no matter how bizarre or counterintuitive they may be, and the most ruthless skeptical scrutiny of all ideas, old and new. This is how deep truths are winnowed from deep nonsense. — Carl Sagan

Deming Lesson #4: Psychology

We are human beings. To improve systems created by human beings, we must understand human beings. We must understand that within a system of human beings, there will always be variation — everyone is different — and that if we wish to improve our systems, we must study the human mind and apply the knowledge we gain to our systems to produce better outcomes.

The study of motivation is an important example of this. There is extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. The former involves being given something to do something, and the latter is when something is its own reward. We know how these work, but we don’t leverage this knowledge within our economy.

Example: Paying someone to do something can actually destroy motivation.

This is one of the most robust findings in social science, and also one of the most ignored. I spent the last couple of years looking at the science of human motivation, particularly the dynamics of extrinsic motivators and intrinsic motivators. And I’m telling you, it’s not even close. If you look at the science, there is a mismatch between what science knows and what business does… That’s actually fine for many kinds of 20th century tasks. But for 21st century tasks, that mechanistic, reward-and-punishment approach doesn’t work, often doesn’t work, and often does harm. — Dan Pink

Meanwhile, the relatively new study of neurogenesis provides a truly incredible example of the damage we are doing.

Example: Poverty and extreme inequality destroy minds.

The structure of our brain, from the details of our dendrites to the density of our hippocampus, is incredibly influenced by our surroundings. Put a primate under stressful conditions, and its brain begins to starve. It stops creating new cells. The cells it already has retreat inwards. The mind is disfigured. The social implications of this research are staggering. If boring environments, stressful noises, and the primate’s particular slot in the dominance hierarchy all shape the architecture of the brain — and Gould’s team has shown that they do — then the playing field isn’t level. Poverty and stress aren’t just an idea: they are an anatomy. Some brains never even have a chance.

If as humans, we are to improve our systems in the present and for the future, we must seek out these kinds of scientific findings and actually apply them.

These four primary lessons are what Deming referred to as a *“System of Profound Knowledge.*” This system provides a map for understanding human systems.

So now that we’ve got such a map, what do we do with it?

... Continued in "How We Can Transform America’s Broken Economic System to Work for EVERYONE"

You can learn more about systems thinking and how to continually improve quality for everyone by reading "The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education" by W. Edwards Deming

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.