The Story of George McGovern's Failure to Guarantee Every American $1,000

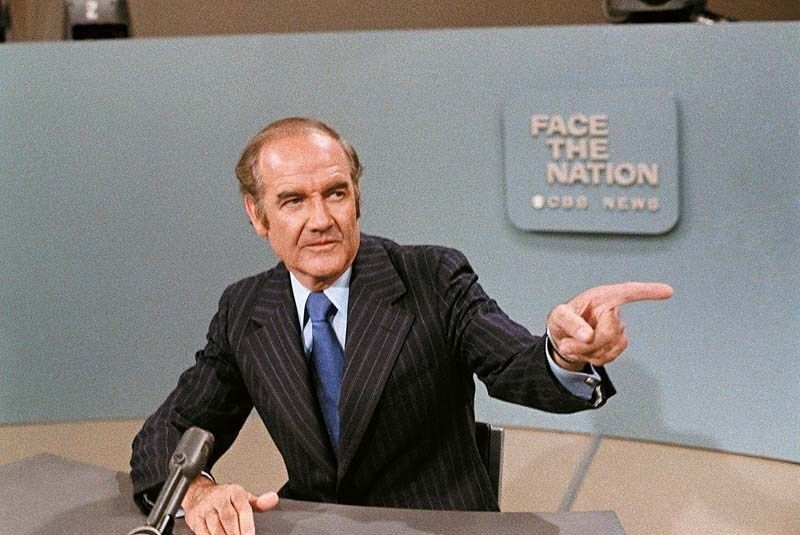

It’s presidential debate season time here in 2019, and in doing my research for an editorial I wrote for Basic Income Today about Andrew Yang’s first debate appearance, I gained some fascinating new insights about what happened back in 1972, which until now was the last time a basic income guarantee was seriously debated in this country. What happened to the idea? Why did it die? Well the answer is actually connected to the transformation of the Democratic party itself after the loss of George McGovern, and it is the story around McGovern’s campaign that I share with you now. Simply put, basic income was mortally wounded when McGovern debated Hubert Humphrey on a Democratic primary debate stage on May 28, 1972.

To fully appreciate what happened that fateful night, we need to go back a bit further. The idea of an income guarantee for all Americans was on the rise in the 1960s. Although the idea of a basic income has a rich history in the US, going as far back as Thomas Paine and his “groundrent” to pay for every citizen’s “natural inheritance”, it was Milton Friedman whose inclusion of a negative income tax (NIT) in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom that really helped bring it to the halls of Washington, D.C. By 1968, discussion around a guaranteed annual income had grown so large that MLK was planning the Poor People’s March upon it, and more than 1,000 economists from 125 universities signed a statement in support of it. Not too long after, a plan was pitched to President Lyndon Johnson to propose, which he declined in favor of skills training and education, and the plan went on to be pitched instead by the new President Richard Nixon in 1969.

Nixon’s plan came to be known as the Family Assistance Plan (FAP). It was essentially a negative income tax for families that would have provided nothing to adults without children. As it worked its way through Congress, a work requirement was attached to it that would have removed some of the total as punishment, but it passed the House of Representatives in both 1970 and 1971. It never made its way through the Senate to be signed by Nixon into law, but if it had, a family of four with two kids could have been guaranteed $1,600 per year in cash, which in today’s dollars is about $11,000, and for every dollar earned, they’d have lost 50 cents of it. Why the FAP couldn’t make it past the Senate is its own story and even its own mystery, but simply put, Democratic Senators wanted a much higher amount and Republican Senators were concerned about family breakup rates, erosion of self-reliance, and the potential for workers to be unwilling to do unpleasant work without wage increases.

Despite the death of FAP in the Senate, large negative income tax experiments would go on for the rest of the decade in cities across America including Seattle and Denver, but it was in 1972 that an idea much closer to universal basic income was proposed. In January of that year, Goerge McGovern proposed a “demogrant” of $1,000 annually to every American as a guaranteed annual income. Unlike Nixon’s FAP, the $1,000 guarantee was for every man, woman, and child. Where Nixon proposed $1,600 for a family of four with a 50% clawback, McGovern proposed $4,000, which in today’s dollars would be $25,000, with a 33% clawback.

The McGovern plan was a retooling of a previously failed plan he had proposed in 1970 that he called the Human Security Plan (HSP). The HSP was a child allowance that would have provided $50 per month for every child ($338/mo in 2019), a guaranteed job for every adult, a Social Security boost that would provide a minimum of $100/mo to ever senior ($678/mo in 2019), and a Special Public Assistance plan for those with disabilities. McGovern’s HSP went absolutely nowhere in Congress, so in 1972 not too long after he began his Presidential campaign, he proposed his demogrant instead. Unfortunately for him, and perhaps even the rest of the world historically speaking, he lacked the computing power to model it.

On the night of their debate, McGovern took the stage against Humphrey with no real understanding of what the net distributive impact of his demogrant looked like, and so when Humphrey attacked it upon claims it would increase the taxes of middle class families earning $12,000 by $400 ($75,000 by $2,500 in 2019), McGovern couldn’t defend it. He thought Humphrey knew more than he himself did, so he didn’t push back. When one of the moderators responded in complete surprise, "But you're asking us to accept a program that you can't tell us how much it's going to cost," McGovern answered, "That's exactly right." What McGovern and Humphrey both didn’t know, and what Nixon did know thanks to the resources available to him as President, is that the bottom 70-80% of families would pay less under McGovern’s demogrant than under existing law or Nixon’s FAP. Households wouldn’t start paying higher taxes under McGovern’s plan until they earned more than $20,000 ($125,000 in 2019).

Humphrey had been wrong, but it didn’t matter. The damage was done. Humphrey had successfully painted McGovern’s demogrant as an unaffordable tax on the middle class. Humphrey also framed it as a pure UBI where everyone would get it, rich and poor alike, when the actual plan had a clawback of 33 cents on every dollar, such that a $12,000 household of four would get $0 of the demogrant. McGovern did not push back against this point either. Viewers watching the debate walked away with the belief the demogrant would not benefit them despite being told everyone would get it, because they thought their taxes would go up too much to pay for it.

McGovern ended up winning the nomination, but in the usual twist of irony that history so loves to display, it was Nixon himself who attacked McGovern as wanting to put 47% of the country on welfare, and that if you weren’t in that 47%, you’d be paying for it. Again, he knew that wasn’t true. He simply used Humphrey’s attack that everyone already believed.

That’s right... Nixon, the guy that history remembers as almost getting an income guarantee passed in America, went after McGovern’s superior income guarantee as being welfare. McGovern dropped the idea completely, went back to the drawing board, and came back with a standard negative income tax focused on the poor, the disabled, and seniors.

Months later, Nixon’s FAP died in the Senate, and in November, Nixon won in a landslide with McGovern winning only Massachusetts and D.C. The loss was so huge that it gave birth to neoliberalism. The lesson many Democrats decided to take away was not that McGovern should have been better prepared to defend ideas like his demogrant, or that a massive loss in 1972 could not have been avoided by any Democratic candidate, but that McGovern had simply gone too far left. That belief has stuck with the Democratic establishment until this day.

In Joshua Mound’s “What Democrats Still Don’t Get About George McGovern” published in The New Republic in 2016, he makes the case that what Democrats should have learned from McGovern’s loss was the same thing Republicans learned in Barry Goldwater’s loss. Republicans didn’t see Goldwater as wrong. They saw him as the one true standard bearer. Goldwater inspired countless Republicans, including Reagan, who went on to win his own landslide election. Seen from this perspective, McGovern was as right about his demogrant as he was about tax-funded single-payer health care and the closing of tax loopholes for the rich. He wasn’t too far left. The country just wasn’t ready yet.

Here in 2019, I think we’re ready now. I think Andrew Yang is bringing back universal basic income at the perfect time, and framing it as it should be framed, a Freedom Dividend for the stakeholders of America, the citizens, that should be paid for by all the massive corporations like Amazon who are paying $0 per year in federal income taxes. Technological advancements should benefit everyone, not just the few.

We’ll see if Andrew Yang can successfully make that case where George McGovern could not, but regardless of what happens, and whether history repeats or we finally move forward, I think the idea of UBI is here to stay this time until it’s finally enacted. As automation forces our hand, the demand for UBI will grow, and at some point, any politician who doesn’t support UBI will suffer political losses that would shock even McGovern.

This post was inspired by an article published in 1973 for The Crimson, "Are You Kidding, George? $1000 Per Person?" which I highly recommend everyone read next who enjoyed reading this.

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.